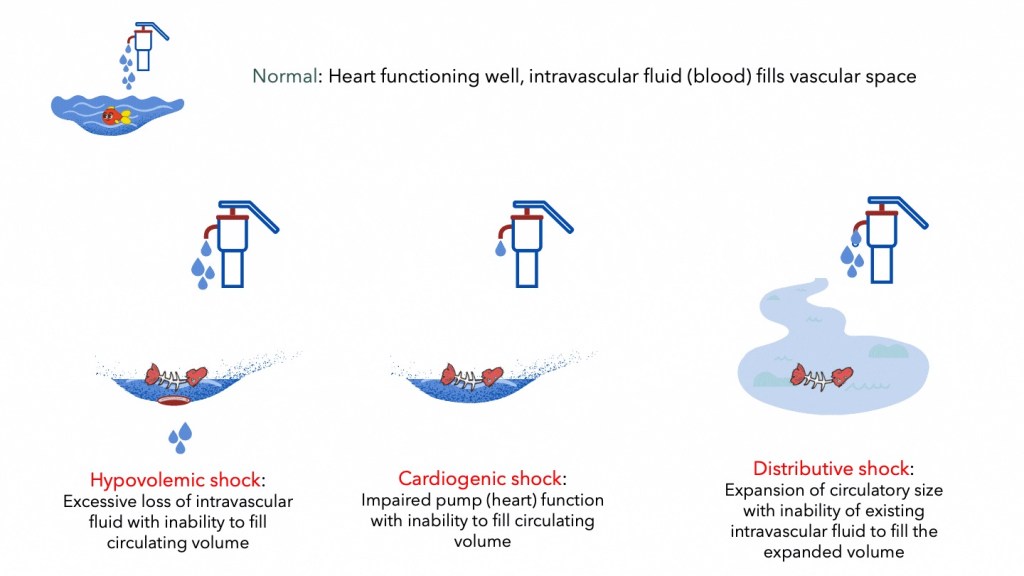

Blood must continuously flow in a circuit. If we take plumbing and water supply as an analogy, water can only be supplied to your home if the reservoir (blood volume) is filled, the main pump (heart) works efficiently and the circuit (vasculature and peripheral resistance) that delivers water is of appropriate calibre and pressure. Failure of any of these components will result in disruption of supply.

In the human body, disruption of the analogous components, results in a clinical condition termed ‘shock’. Recognising shock early in its course is important as early aggressive intervention is required, failing which the patient will progress to irreversible shock and death.

Learning outcomes

- Define shock

- Differentiate the causes of cardiogenic, hypovolemic, distributive and obstructive shock

- Explain the basic pathophysiology and compensatory mechanisms of the different forms of shock

- Describe the clinical signs and consequence of shock

Definitions and basic physiology

Conceptually, shock is attributable to circulatory failure that results from a discrepancy in the size of the vascular bed and the volume of the intravascular fluid (Blalock, 1940). This can lead to insufficient blood to fill the arterial tree under sufficient pressure to provide organs and tissues with adequate blood flow

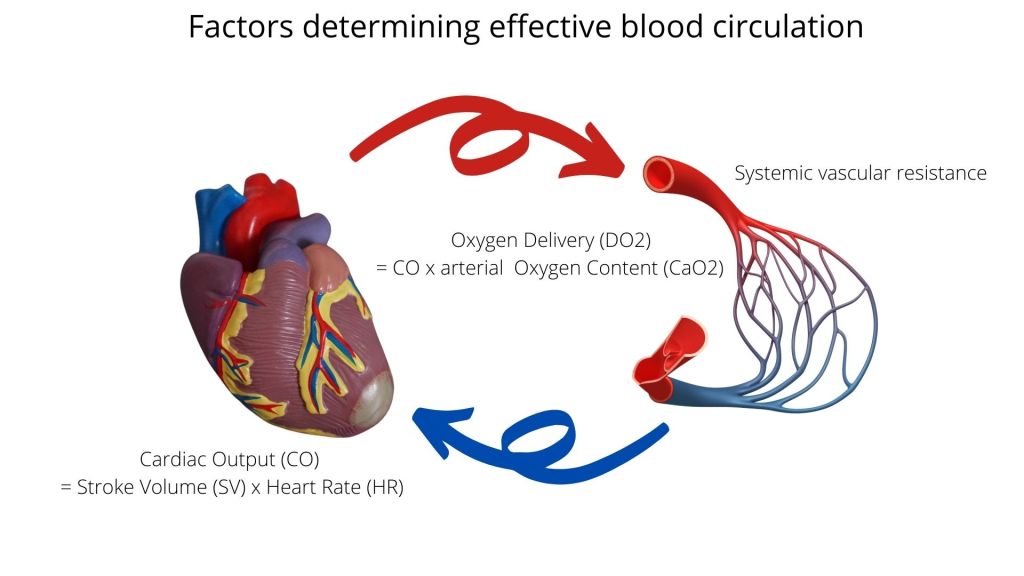

Adequate blood flow and oxygen delivery to meet tissue needs is affected by at least three components of the circulatory system.

- Cardiac output

- Circulating blood volume and total oxygen content

- Resistance to flow and size of vascular bed

Cardiac output (CO) is the volume of blood ejected by the heart per minute, and is determined by the stroke volume (SV) and heart rate (HR) i.e. CO = SV x HR. The control of SV is meanwhile dependant on several factors that include;

- Preload – the degree of stretch produced across the ventricular wall at the end of diastole, and its effect on the force of ventricular contraction. Affected in cardiac failure, ischaemia and hypovolemia

- Afterload – resistance or load against which the ventricle must eject against or overcome in order to cause blood to flow forwards into the aorta. Mainly determined by arterial pressure. May also be reduced by fixed obstruction such as aortic stenosis or a large embolus.

- Contractility – ability of the ventricle to contract (systolic function) and relax (diastolic function).

The size of the intravascular bed and pressure gradient meanwhile can be altered when there is vasodilation and arteriolar dilatation. This occurs when there are vaso-inhibitory substances produced as in endotoxinaemia or when there is loss of vascular tone control as in anaphylaxis or some neurologic conditions.

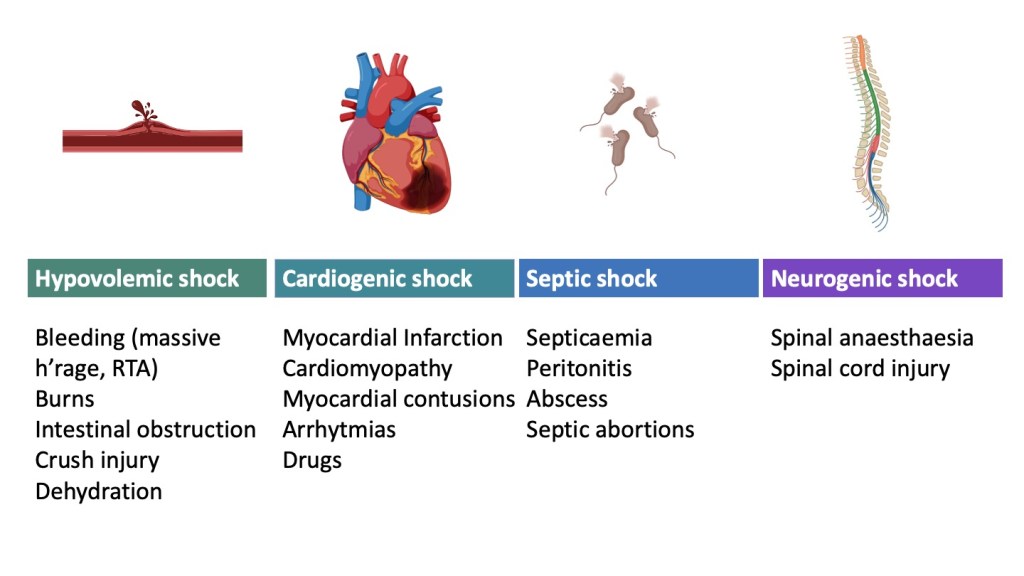

Classification of shock

1. Cardiogenic shock

Cardiogenic shock is essentially pump failure that usually results from acute myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmia, valvular heart disease or myocarditis.

The onset of cardiogenic shock is accompanied by a drop in SV and consequently CO, as well as reduced blood pressure (BP). In order to maintain CO, the HR may be increased by sympathetic action. The clinical signs associated with this is tachycardia and hypotension.

The reduction in blood flow and perfusion leads to reduced DO2 at the capillary level and mean arterial pressure. Compensatory mechanisms kick-in, in an attempt to maintain blood pressure through vasoconstriction, and blood volume, by increasing cathecolamines (adrenaline, noradrenaline), activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and the anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) pathways.

Clinically the patient may present with cold and clammy skin due to peripheral vasoconstriction. Reduced urinary output occurs due to reduced renal perfusion and increased ADH.

2. Hypovolemic shock

Hypovolaemic shock results from inadequate circulating volume. This is usually due to massive bleeding following trauma, obstetric and gynaecological incidents or surgical complications.

Similar to cardiogenic shock, hormonal and neurogenic compensatory mechanisms cause vasoconstriction and fluid retention to attempt to maintain blood pressure up until the point of becoming overwhelmed.

Signs associated with hypovolemic shock include tachycardia, hypotension, cold and clammy skin and anuria.

3. Distributive shock

Distributive shock is characterised by excessive arteriolar vasodilatation that leads to a decrease in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and severe hypotension.

In contrast to cardiogenic and hypovolemic shock, distributive shock is usually described as “warm shock” because the peripheries are warm and sweaty in this this form of shock, as compared to cardiogenic and hypovolemic shock where the extremities are cold and clammy. This is because there is vasodilatation instead of vasoconstriction in distributive shock.

Septic shock due to bacterial septicaemia is the most common type of distributive shock. Bacteria, particularly of gram-negative type produce endotoxins that cause a systemic inflammatory response (SIRS) and widespread arteriolar vasodilation, throwing the patient into shock.

Other types of distributive shock is anaphylactic shock and neurogenic shock.

In anaphylaxis, there is massive mast cell degranulation with release of histamine and other vasoactives in response to an IgE- related stimulus (Type-1 hypersensitivity) which reduces vascular tone and increases capillary leak.

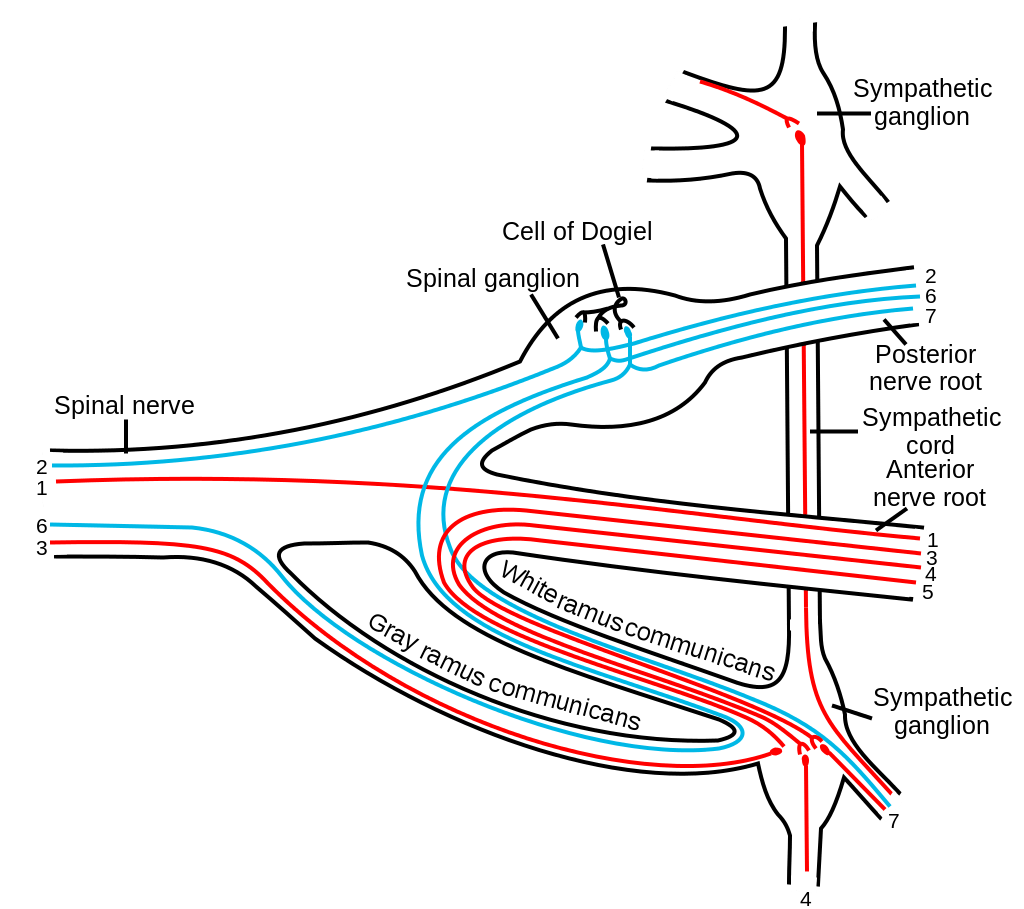

Neurogenic shock usually occurs following thoracic spinal cord injury with subsequent loss of sympathetic outflow causing loss of vascular tone.

4. Obstructive shock

Obstructive shock occurs when there is physical obstruction to the blood flow at the level of the great vessels of the systemic or pulmonary circulation. Causes include massive pulmonary embolism, cardiac tamponade, aortic stenosis and tension pneumothorax.

The following link provides additional information and illustration of the different forms of circulatory shock (N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1726-1734 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1208943) .

Sequelae and complications

Progressive shock results in redistribution of blood flow to the vital organs such as the heart and brain at the expense of other organs such as kidney, muscle, splanchnic and liver. The consequence of this is the clinical features of cool extremities, oliguria, membrane pallor, delayed capillary refill time, weak pulses, and reduced level of consciousness.

Other consequences of tissue hypoxia and eventual cell death include,.

- Failure of aerobic respiration and accumulation of lactic acid (lactic acidosis) due to anaerobic glycolysis.

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation as a complication of tissue damage and coagulation activation, especially in septic shock and trauma associated hypovolemic shock.

- Acute tubular necrosis with consequent anuria and acute renal failure

- Centrilobular hepatic necrosis leading to liver failure

- Adrenal haemorrhage and necrosis

- Acute lung injury

- Progressive loss of consciousness due to reduced cerebral perfusion

- Myocardial ischaemia from reduced coronary perfusion