Anaemia is a condition when the haemoglobin concentration is lower than expected ie. below the reference range for a population of similar age and sex. As explained in the previous module, the normal haemoglobin concentration varies according to age groups and gender.

Anaemia is often asymptomatic, Chronic anaemia however poses a significant threat to satisfactory childhood motor and cognitive development. In the adult, it limits productivity and is contributory to excess morbidity and morbidity especially when in pregnancy and in the presence of co-morbid conditions. WHO estimates that globally, up to one third of women of reproductive age and 40% of children under the age of 5 years are anaemic.

Learning outcomes

- Define anaemia

- Develop a classification system for anaemia based on physiological and morphological approaches

Clinical features

The normal human body has a large reserve of haemoglobin to cope with sudden increase in demands for oxygen delivery. The bone marrow can also increase its output of red cells and haemoglobin up to six times the basal level when there is a need to push up production to compensate for an increase in oxygen demand (e.g. high altitude) or if there is a drop in haemoglobin (e.g. bleeding, haemolysis).

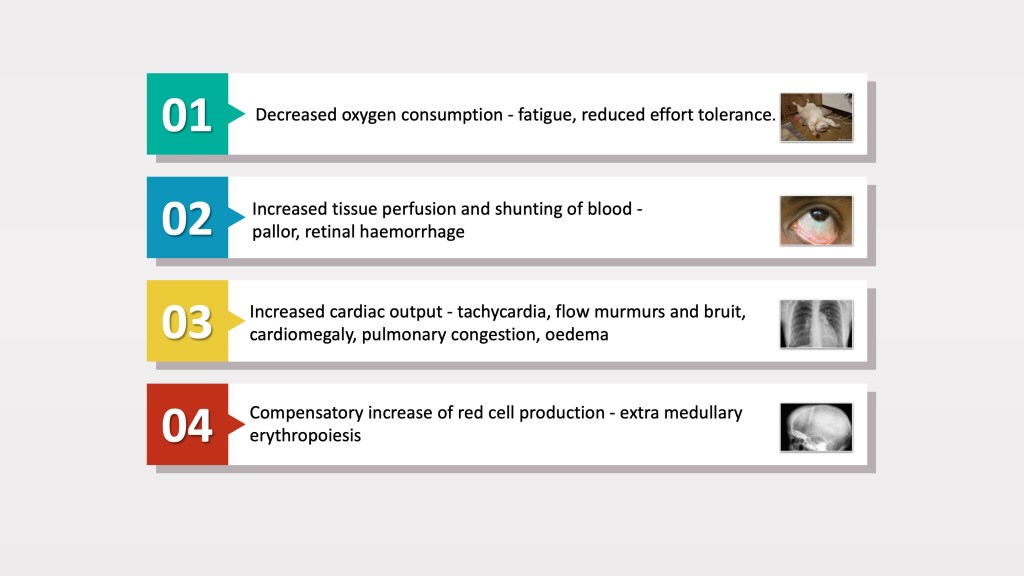

Clinical symptoms associated with anaemia usually develop when the bone marrow is unable to compensate for the haemoglobin drop. In order to ensure continued delivery of oxygen, sufficient for organ demands, cardiac output needs to be increased. This is reflected in a hyper-dynamic circulation as evidenced by tachycardia, cardiac murmurs and in extreme cases, decompensated congestive cardiac failure. Reduction in tissue oxygen delivery may result in lethargy, poor effort tolerance and reduced cognition. Vasoconstriction of peripheral blood vessels in order to maintain circulation and oxygen delivery to central organs such as the heart and brain, results in the physical appearance of pallor.

In poorly managed chronic anaemias of childhood (e.g. thalassaemia) , increasing haematopoiesis to cope with red cell demands may result in widening of the medullary spaces, bossing of the forehead and hair-on-end appearance. Extra-medullary haematopoiesis may occur in children and adults and is characterised by hepatosplenomegaly.

Physiological classification of anaemia

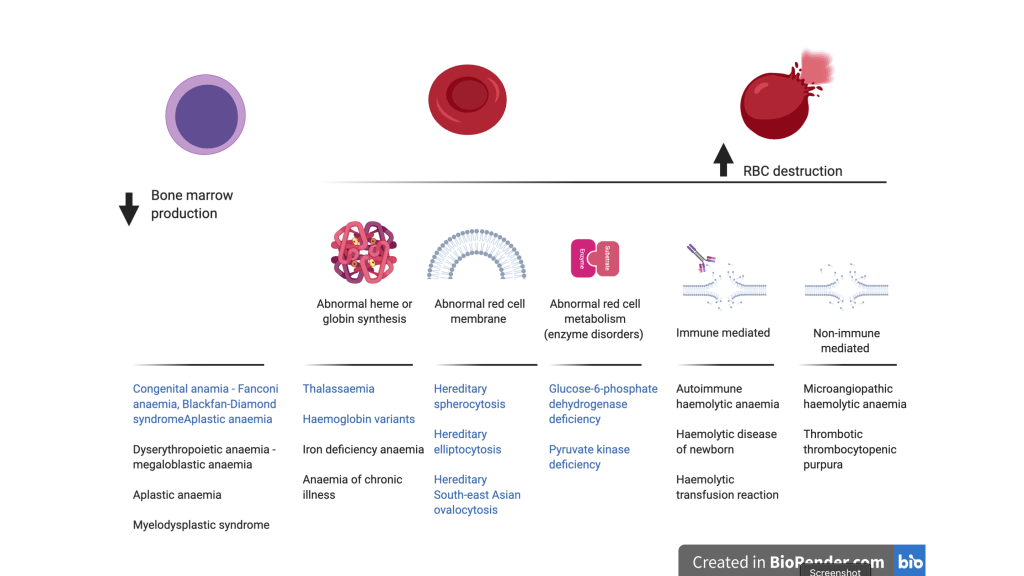

Many conditions can contribute to anaemia. In simple terms, anaemia may either occur due to:

- Failure of erythropoiesis or production of normal red cells in the bone marrow

- Excessive loss or destruction of red cells in circulation i.e. haemolysis

This is illustrated by the figure below that show some congenital (text in blue) and acquired (text in black) causes of anaemia. The cause of anaemia may also be multifactorial, especially in ill patients.

Morphological classification of anaemia

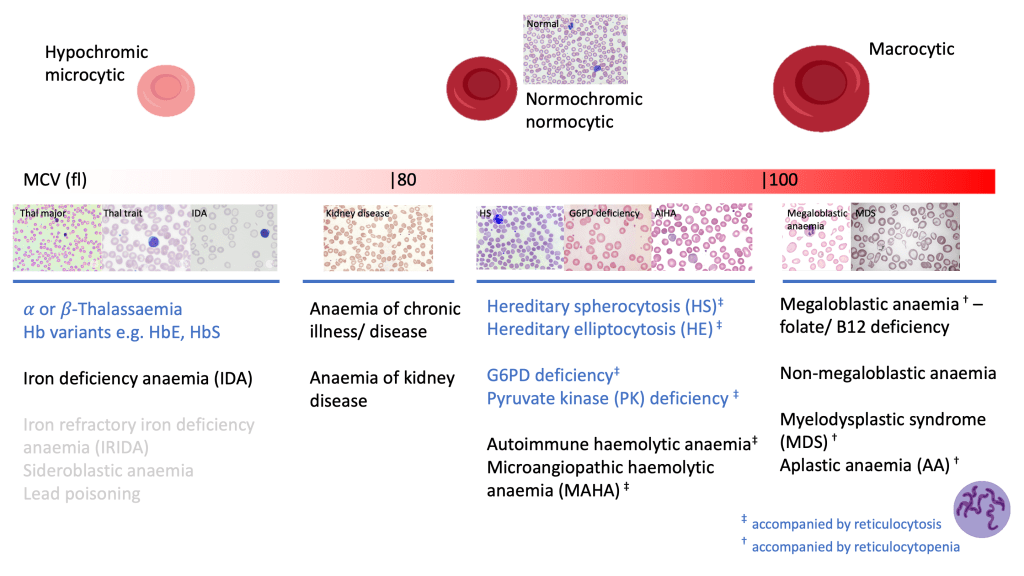

A simple classification of anaemia based on its underlying pathophysiology as explained above is useful in understanding the disease process and instituting appropriate management of the anaemia. Nonetheless, in clinical practice, the classification of anaemia based on red cell size and haemoglobin content, as evidenced by the mean cell volume (MCV) and mean cell haemoglobin (MCH) respectively is a useful approach for identifying the cause for the anaemia.

Using MCV as a parameter, anaemia therefore can be classified into:

- Microcytic anaemia

- Normocytic anaemia

- Macrocytic anaemia

The other full blood count (FBC) parameters such as red blood count (RBC), red distribution width (RDW) and reticulocyte count, provides further useful information to narrow the cause of the anaemia. The figure below illustrates the differential diagnosis for the cause of anaemia, inferred from MCV and whether there is accompanying reticulocytosis or reticulocytopenia.

Of course, it must be understood that the differentiation of causes of anaemia based on these values is not absolute but only serves as a guide for further investigations.

Hypochromic microcytic anaemia

The two most common cause for microcytic anaemia in Malaysia is thalassaemia and iron deficiency anaemia. Both conditions are usually suspected incidentally on performing a FBC as they are generally asymptomatic unless severe. Thalassaemia carriers however usually show normal or high RBC with less severe anisocytosis as evidenced by normal or mildly increased RDW. This contrasts with iron deficiency anaemia which shows low RBC accompanying the low MCV and MCH while the RDW is high.

Both iron deficiency and thalassaemia co-occurring in a patient is also not uncommon as the prevalence of both conditions is high in our population. In some patients, other confounding factors such as anaemia of chronic disease, renal disease and liver disease may coexist. This often complicates the distinction of the various conditions using FBC parameters alone. All these condition will be elaborated further in subsequent learning modules.

Macrocytic anaemia

Macrocytic anaemia is less common in Malaysia as compared to the other former of anaemia. Marked macrocytosis (MCV > 120 fl) is often associated with megaloblastic anaemia secondary to folate or vitamin B12 deficiency. Milder forms of macrocytosis (MCV 100 – 120 fl) can be due to megaloblastic as well as non-megaloblastic causes. More details on megaloblastic and non-megaloblastic conditions will be provided in the subsequent learning modules.

In older patients, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which is considered a precursor to leukaemia can present as macrocytic anaemia, but is usually accompanied by abnormalities of the white cells and platelets too. MCV may also be elevated in aplastic anaemia (AA), a stem cell disorder that causes pancytopenia. Both MDS and AA will show low reticulocyte count.

Normochromic normocytic anaemia

This form of anaemia has many underlying causes which can be attributed to increased peripheral red cell destruction (haemolysis) or disturbances in red cell maturation or production.

Haemolysis is usually accompanied by an increase in reticulocyte count (reticulocytosis), jaundice and biochemical evidence of heme breakdown . The triad of anaemia, jaundice and reticulocytosis is classical for haemolytic anaemia. Haemolytic anaemia and the various conditions associated with it will be covered in a subsequent learning module.

In patients, normochromic anaemia without significant reticulocytosis is often due to multifactorial conditions associated with their underlying disease. Renal and liver impairment as well as chronic infections and malignancies may contribute to impaired red cell production presenting as normocytic or mildly microcytic anaemia.