Total blood volume (TBV)

The total blood volume (TBV) of an adult is estimated at about 70 ml/kg. Estimated TBV may differ depending on lean body mass content. The higher the body fat content, the lower is the blood volume per unit mass. A simple estimate of TBV may be as follows;

- Average adult: 70 ml/kg

- Muscular adult: 75 ml/kg

- Neonates and infants: 80 ml/kg

A more accurate estimate may be based on Nadler’s equation

Composition of blood

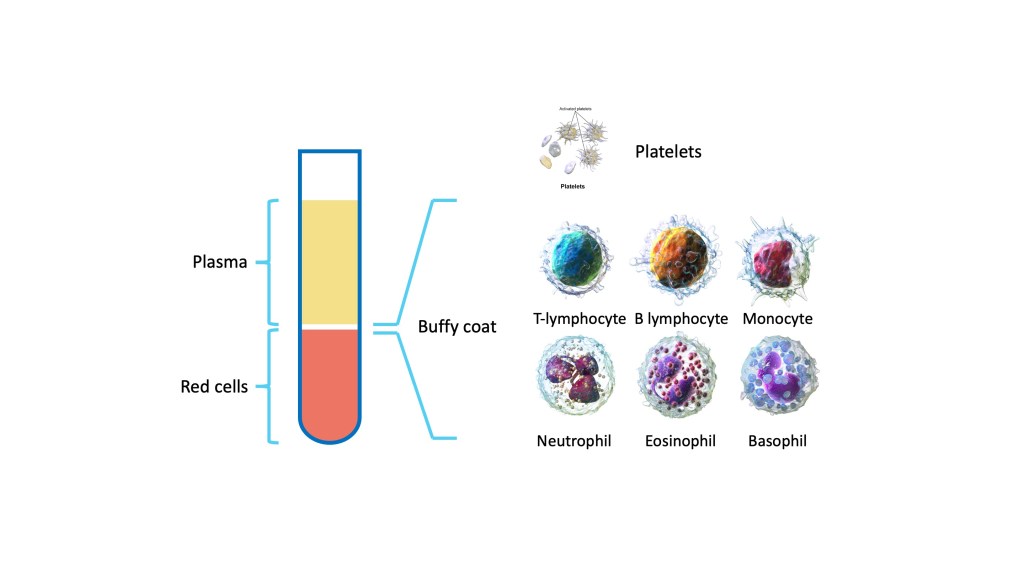

Anti-coagulated blood when left to stand or centrifuged will separate into two visually separate compartments; liquid plasma and the cellular component. The plasma portion is mainly composed of water, electrolytes and proteins.

The major components of the protein fraction are albumin and globulins. Other minor but essential proteins include hormones, cytokines and transport proteins. Various coagulation factors are also present in the protein fraction. if blood is not anti-coagulated and allowed to clot, the coagulation factors will be activated, subsequently converting fibrinogen into insoluble fibrin. The remaining liquid portion is then termed as serum.

The cellular component sediments according to each cell’s specific gravity. The densest cells in normal blood are the red cells. The white cells are less dense than the red cells and therefore ‘float’ on the red cells and this is known as the buffy-coat. Among the white cells, granulocytes which includes neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils are denser than lymphocytes and therefore can be separated from lymphocytes, monocytes and other mononuclear cells (PBMC) by a process of density gradient centrifugation. Platelets are the smallest and least dense of blood cells and therefore are found at the cell-plasma interface.

Red blood cells (RBC, erythrocyte)

RBC are the major cellular constituent of blood. In a healthy adult, 42-50% of the total blood volume consists of RBC. The proportion of red cell volume to whole blood volume is termed as the ‘haematocrit‘. RBC are also the most abundant cell in the human body. A litre of blood contains about 5 x 1012 RBC in a normal adult male.

Red blood cells are non nucleated biconcave cells. The structure and content of human RBC have evolved to serve its functions efficiently.

Red cells have multiple functions, the most important of which is oxygen carriage and transport. Oxygen carriage is facilitated through the binding of oxygen to the highly specialised oxygen carrying molecule, haemoglobin. Other important functions of red cells include;

- Transport and excretion of carbon dioxide

- Nitric oxide metabolism and regulation

- Redox regulation

- Regulation of blood viscosity and flow

Further information on aspects of RBC related to specific disorders will be covered in subsequent modules.

Platelets

Platelets are non-nucleated cells derived from the cytoplasmic shedding of megakaryocytes that reside in the bone marrow. Next to RBC, platelets are the second most abundant cells in the human body. A litre of blood contains 150-400 x 109 platelets.

Platelets are small cells (1-2 um) that circulate as biconcave structures. When activated, platelets can undergo shape change to spherical form with pseudopodia formation. On activation, they can express and secrete various proteins and chemical mediators that facilitate control of bleeding (haemostasis).

Platelet structure and function will be elaborated further in the module on bleeding disorders.

Leucocytes (White blood cells)

White blood cells are circulating nucleated cells in blood that are important players in both innate and adaptive immunity. In a normal adult, the total white blood count (TWBC) is 4 -11 x 109/L. Reference ranges may however vary among different populations and age groups. It is therefore important for you to refer to the reference range provided by the laboratory in the hospital you are working in and the patient’s age when interpreting results of blood counts.

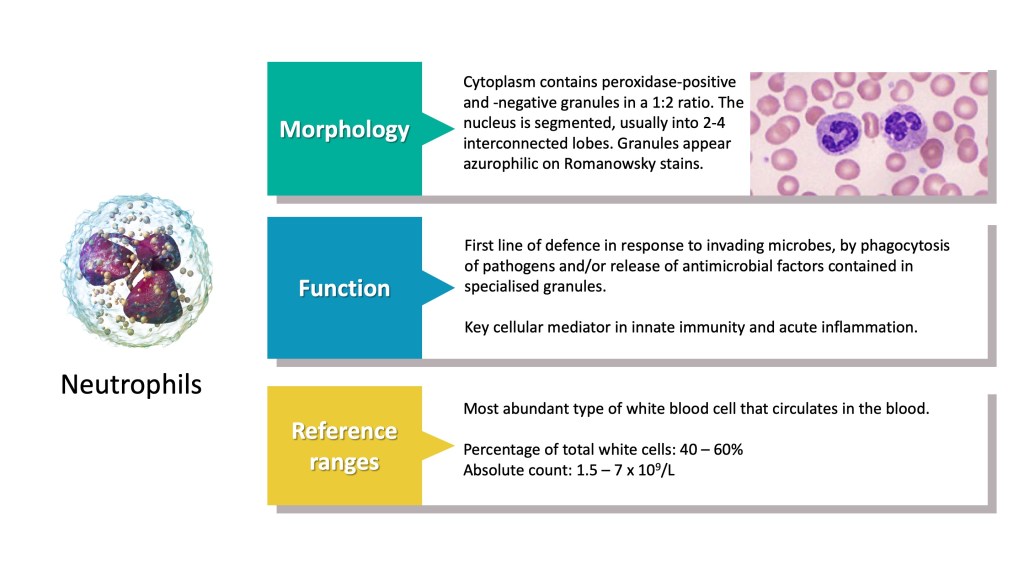

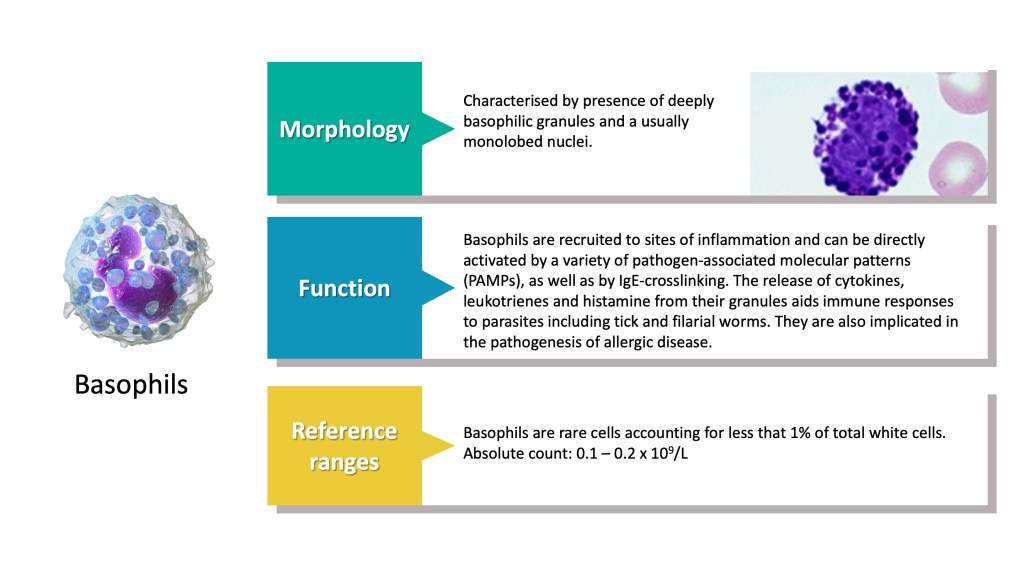

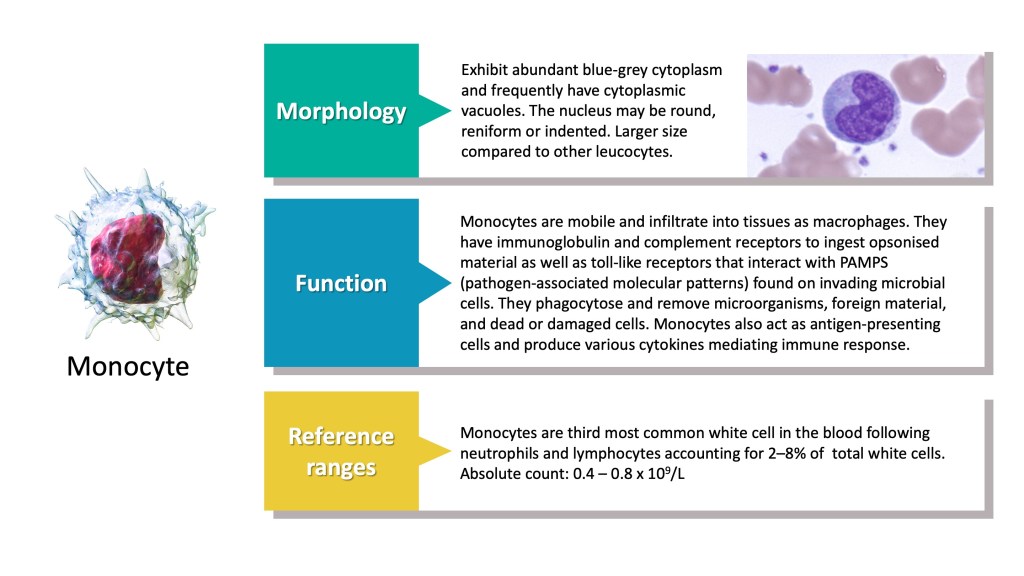

There are five types of leucocytes that can be seen circulating in blood; neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils and basophils. The cells are distinguished by their size, nuclear appearance and cytoplasmic contents. Neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils are characterised by cytoplasmic granules. These cells are called granulocytes. Monocytes and lymphocytes generally do not have visible granules.

Neutrophils are key cellular players in innate immunity and acute inflammation. Neutrophils are capable of phagocytosis and microbial clearance. In addition, neutrophils can release various antimicrobial chemicals from their granules. Eosinophils also contain granules and they are important mediators involved in parasitic infections and allergic reactions. Basophils meanwhile have histamine containing granules and often mediate hypersensitivity reactions.

The agranular monocytes have phagocytic capability and are important for microbial clearance. Upon phagocytosis, monocytes are capable of processing the phagocytosed microbes to smaller peptide fragments. They can then present the fragments on their surface MHC Class II molecules for recognition by T-cell receptors of the T-lymphocytes. In this manner, they act as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. They also release various cytokines that further recruit T and B-lymphocytes.

Lymphocytes meanwhile are composed of B and T-lymphocytes. B-lymphocytes are involved in the humoral arm of adaptive immunity and can differentiate into antibody producing plasma cells and long-term memory B-lymphocytes. T-lymphocytes meanwhile have complex roles in initiation and regulation of cell-mediate immune response of adaptive immunity.