Iron is an essential element for cellular functioning of nearly all prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Humans have evolved to conserve iron, to the extent of hoarding it, as it is scarce in nature and the process of acquiring iron is energy intensive. Although iron is abundant geologically, it often exists as highly insoluble oxides when coming in contact with environmental oxygen and thus is not readily available for uptake by organisms.

Learning outcome

- Explain iron homeostasis and its absorption, transportation and utilisation by cells

- Relate the changes to components of iron homeostasis in relation to iron deficiency states

Once iron is absorbed, there is no physiological mechanism for excretion of iron from the body. The daily loss of iron is limited to the sloughing of iron-containing enterocytes into faeces. In women of reproductive age, menstrual blood loss also contributes to iron loss. Dietary requirements for iron need to replenish the iron that is lost through these routes.

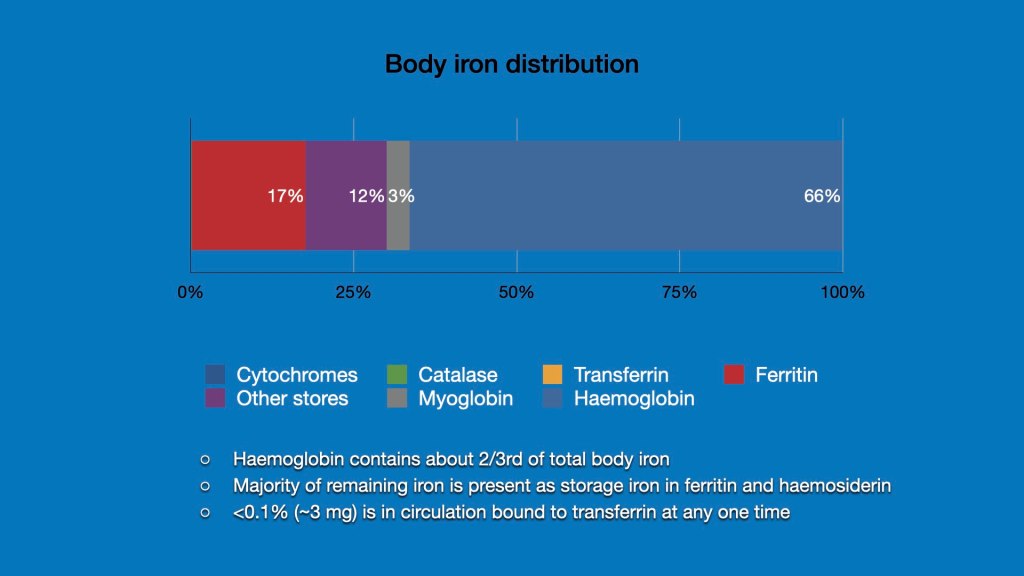

Iron is an essential cofactor for many cellular processes through its incorporation into various chemical structures that act as transport proteins, co-factors and enzymes. Their physiological function and examples of corresponding compounds include:

- Oxygen transport – haemoglobin, myoglobin

- Respiration and mitochondrial function – cytochromes

- Gene regulation and DNA synthesis – ribonucleotide reductase

- Innate immunity – catalase

As much as iron is essential for life, iron can also be toxic to cells at high concentrations. It is therefore not surprising that the human body has developed a tightly regulated iron homeostatic mechanism.

The iron circuit

The average amount of iron in an iron replete adult ranges from 3-4 g. The iron is distributed in various tissues with the majority present in the liver as storage iron and bone marrow and red cells as a component of haemoglobin. Over 2/3rd or the total body iron is present within haemoglobin.

Iron is strictly conserved and regularly recycled from the breakdown of red cells at the end of their life. In healthy adults, 20 to 25 mg of iron cycles daily.

Iron is lost daily from the sloughing of intestinal mucosal cells. This loss is limited to 1-2 mg of iron daily. Iron intake from the diet balances this loss of iron. The bioavailability of iron is only about 10-20% and is regulated at the level of the enterocyte. The usual adult diet therefore needs to contain contains about 10-20 mg of elemental iron daily. Women of reproductive age will require higher intake to balance iron loss from menstruation.

The majority of iron in the daily cycling pool comes from the splenic macrophages that phagocytose senescent red cells and process their heme to release the Fe(II). Iron may also be mobilised from ferritin stores in the liver. The dietary, recycled and mobilised iron is distributed to the various cells that require require iron, the most important of which are the erythroid cells in the bone marrow and the macrophages of the liver.

Dietary source of iron

Dietary iron may be available in two forms:

- Heme iron, derived from animal food sources (meat, seafood, poultry), which is the more easily absorbable

- Non-heme iron, derived from plants and iron-fortified foods and is less-well absorbed

The presence of phytates, oxalates, phosphates, carbonates, and tannates decreases non-heme iron absorption. For example, spinach is a rich source of iron but it also contains oxalates that can limit the availability of iron for absorption. Tea contains tannates and polyphenols, and its high intake may reduce iron absorption.

Conversely, the absorption of non-heme iron is increased by ascorbic acid, protein in the diet, and a low gastric pH that fosters more efficient digestion of food. Hypo- or achlorhydria, which results in higher gastric pH, reduces iron release from food. Dietary iron can be bound to antacids, starch or clay, inhibiting absorption.

Absorption and utilisation of iron

Iron is absorbed in the duodenum and proximal jejunum. Prior digestion within the acidic environment of the stomach improves the uptake of iron by the the enterocytes. Causes of hypo- or achlorhydria such as atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, gastrectomy, treatment with proton-pump inhibitors and vagotomy may reduce iron absorption.

Iron exists is the oxidised, ferric (Fe3+) state at physiological pH. In order to facilitate absorption, iron must be in the ferrous (Fe2+) state or bound by a protein such as heme. The low pH of gastric acid in the proximal duodenum allows a ferric reductase enzyme, duodenal cytochrome B (Dcytb), on the brush border of the enterocytes to convert the insoluble ferric (Fe3+) to absorbable ferrous (Fe2+) ions. Once converted into the ferrous (Fe2+) state, divalent metal cation transporter 1 (DMT1) can transport the iron across the apical membrane and into the cell. Both Dcytb and DMT1 are up-regulated under hypoxic conditions in the intestinal mucosa by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF).

Within the enterocyte, iron can be incorporated into ferritin for storage or transported across the basolateral membrane into the circulation through ferroportin, a transmembrane protein that is crucial for regulation of intracellular iron. Ferroportin is the only way out (efflux route) for cellular iron and the efflux is almost exclusively regulated by hepcidin levels.

Hepcidin can bind to ferroportin and degrade it, hence preventing the release of iron from the cell for entry into the circulation. High levels of iron, inflammatory cytokines, and oxygen cause an increase of hepcidin levels, effectively trapping the iron in the enterocytes which can be sloughed into the faeces. Conversely, low iron state and hypoxia down-regulates hepcidin, thereby allowing iron to be exported out of enterocytes to be utilised by other cells.

The ferrous (Fe2+) iron released from the enterocytes is oxidised again into the ferric (Fe3+) state by hephaestin, to facilitate binding to transferrin, a carrier protein that is present in plasma. Each molecule of transferrin can bind two Fe3+ molecules, to be transported safely in the circulation without formation of reactive oxygen species.

Iron-utilising cells such as erythroid cells express transferrin receptors (TfR). When transferrin binds to the TfR, the complex is internalised by endocytosis. Within the endosome, the iron is release from the complex in a low pH environment, and the ferric Fe3+ iron is reduced to ferrous Fe2+ iron by the transmembrane ferrireductase, steaphaestin. The ferrous Fe2+ iron is then transported into the cytoplasm via DMT1, to be utilised for various cellular processes. In erythroid cells, the iron enters the mitochondria where it is incorporated into protoporphyrin to form heme. In cells such as macrophages and hepatocytes, the iron may be incorporated into ferritin for storage.

Post-transcriptional modulation of cellular iron homeostasis

The cellular expression of many of the proteins involved in iron homeostasis is regulated post-transcriptionally at the translational level. This allows for rapid responses and precise changes in the uptake and utilisation of iron within the cells. Iron responsive proteins that are post-transcriptionally regulated include DMT1, ferroportin, TfR and ferritin.

The control mechanism is mediated through iron regulatory protein (IRP) and iron responsive elements (IRE). IRP are RNA-binding proteins that bind to specific non-coding sequences that are known as IRE within the untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA transcripts. IREs can be present in either the 3′-UTR or 5′-UTR of the target mRNA. Transcripts with IRE motifs in their 5′-UTR include the ferritin and ferroportin, whereas target mRNA with IRE motifs in the 3′-UTR include TfR and DMT-1.

IRP binding to the IRE motif in the 5′-UTR of target mRNA can inhibit translation while IRP binding to IRE motifs in the 3′-UTR stabilises the mRNA and enhances translation.

In cells with adequate iron content i.e. iron-replete, iron can bind with IRPs and prevent them from binding to the IRE motifs of their target mRNA. In the case of ferritin and ferroportin which have IRE motifs in the 5′-UTR, the failure of IRP binding to the IRE releases inhibition and facilitates translation of ferritin and ferroportin, so that excess iron can be diverted to ferritin or exported out of the cell.

in the iron-deficient state, IRPs are conformationally free to to bind to IRE. The binding of IRPs to IREs at the 3′-UTR of TfR and DMT1 transcripts stabilises and promotes translation of the proteins, so that there is enhanced uptake of iron into the cell. Conversely, the binding of the IRP to the 5′-UTR of ferritin and ferroportin represses the translation of both proteins, hence reducing the unnecessary iron binding by ferritin and iron export by ferroportin, eventually leading to increased levels of free iron available for cell utilisation.

Regulation of iron by hepcidin

Hepcidin is produced in the liver and is an important regulator of iron homeostasis through its action on ferroportin. Hepcidin binding to ferroportin causes internalisation and degradation of ferroportin, hence preventing iron release from cells such as duodenal enterocytes and splenic macrophages.

Hepcidin levels can be effected by:

- Inflammatory mediators such as TNF-a and IL-6. These mediators cause increase hepcidin release from the liver and limits systemic iron availability by decreasing ferroportin expression and transport of iron to the outside of enterocytes and splenic macrophages.

- Iron content of hepatocytes. High levels of transferrin saturation as sensed by hepatocyte TfR, and facilitated by HFE, causes release of hepcidin to attenuate further absorption and uptake of iron . Mutations of the HFE gene and loss of iron-sensing signal of TfR causes iron accumulation in Type I haemachromatosis. Increase in cellular iron also causes increase of BMP-6, a protein that binds in an autocrine fashion to its receptor, and together with its co-accessory protein hemojuvelin (HJV) increases hepcidin release.

- Increased erythropoiesis. Enhanced erythropoiesis can release signals that reduce hepcidin secretion, so that more iron is made available for erythroid development.

- Oxygen tension of hepatocytes. Low oxygen tension within hepatocytes induce expression of a membrane protease, matriptase-2, that cleaves HJV, thus blocking hepcidin release via the BMP-6/BMP-6R/HJV circuit. Low hepcidin allows for more iron efflux from enterocytes and splenic macrophages into circulation.

The role of hepcidin in the pathogenesis of anaemias associated with chronic inflammation and malignancies will be explored further in subsequent teaching modules.