Learning outcome

- Describe the causes, clinical features and laboratory features of iron deficiency anaemia

Prevalence and epidemiology

Iron deficiency (ID) remains the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide and is estimated to effect nearly 30% of the global population. In Malaysia, about 5% of schoolchildren between the age of 7 to 12 years are iron-deficient. The prevalence of iron deficiency in pregnant women varies between 20 – 40% depending on the populations studied.

The detrimental public health effects of IDA include retarded infant development, increased morbidity and mortality at childbirth, and reduced work performance. Patients with poorly managed iron deficiency anaemia often have longer hospital stays and poorer clinical outcomes, especially post-surgery and delivery. They are also at higher risk of receiving unnecessary red cell transfusions.

Populations at higher risk of iron deficiency include:

Pregnant women

This is likely the most vulnerable group for ID, as the dramatic expansion of red cell mass to meet the needs of the foetus and placenta requires escalation of dietary and supplemental iron intake. ID during pregnancy increases the risk of maternal and infant mortality, premature birth and low birthweight.

Infants

Full-term infants are at risk of ID at the age of 6-9 months if they are not weaned and started on solid foods that are rich in iron or supplemented with iron fortified formula. Breast milk alone would not be adequate to provide for the rapid infant growth. Preterm and low birthweight infants or those born to mothers with ID are at risk of ID early after birth due to their rapid growth.

Adolescence

Red cell mass shows an increase during the pubertal spurt and teenage years. Among girls, the attainment of menarche poses additional blood loss. This group is vulnerable if dietary intake of iron is not commensurately increased

Women of reproductive age

Heavy bleeding during menstruation poses a risk of ID if dietary intake of iron is unable to meet the demands for increased erythropoiesis.

Frequent blood donor

The risk of ID following blood donation is low as long as the donor ensures adequate dietary intake of iron or supplementation. A single whole blood donation results in the loss of about 200mg of iron. Regular donations at 8 to 12-weekly intervals without adequate supplementation or intake of food with high iron bioavailability may lead to ID.

Patients with comorbid conditions

Patients with gastrointestinal tract tumours often have ID due to chronic blood loss. Functional ID may also be seen commonly among patients with neoplastic and chronic diseases.

Causes of iron deficiency anaemia

The causes of iron deficiency can generally be divided into two main groups

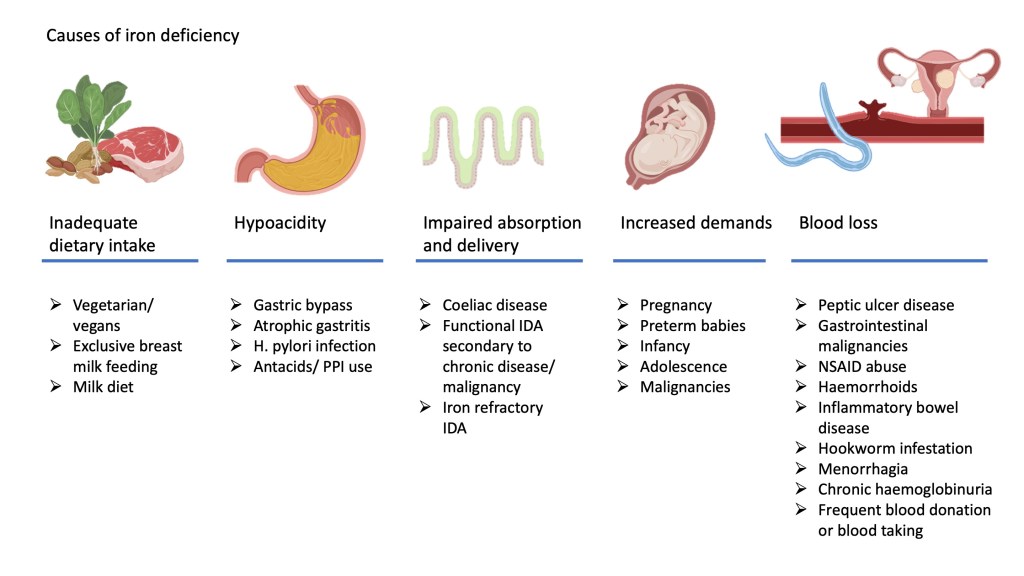

- Inadequate iron intake for distribution in the body. Factors that could contribute to this include inadequate dietary intake, failure of absorption across the intestinal cells into the circulation or abnormalities of iron efflux and intake into cells.

- Excessive utilisation or loss of iron from the body with inability of intake to keep up with demand. This may occur as a result of increased demands in certain vulnerable groups as outlined earlier or abnormal loss of iron containing red cells.

The figure below illustrates some of the causes that contribute to iron deficiency

Clinical features

Iron deficiency anaemia is usually asympthomatic unless severe. As anaemia develops gradually, the body usually compensates for the reduced oxygen carrying capacity by increasing cardiac output and shunting blood to vital organs. General symptoms of anaemia is noted such as lethargy, reduced effort tolerance and dyspnoea. In severe cases, patients may present with decompensated congestive cardiac failure.

Patients with iron deficiency anaemia have been reported to have associations with restless leg syndrome and the unusual eating disorder, pica. Rarely, patients with IDA may present with dysphagia due to formation of oesophageal webs, also known as Plummer-vinson syndrome.

In addition to pallor, patients may show nail changes such as brittle or spoon shaped nails (koilonychia), inflammation of the tongue (glossitis) and inflammation around the angles of the mouth (angular stomatatis).

Laboratory features

Haematological investigations

Iron deficiency anaemia presents as a microcytic anaemia. Anaemia however is a late indicator of iron deficiency as microcytosis will only develop once iron stores have been completely depleted. Iron deficiency in the absence of anaemia is referred to as latent iron deficiency.

Characteristic features of IDA on a full blood count includes:

- Low haemoglobin and haematocrit

- Low mean cell volume (MCV) and mean cell haemoglobin (MCH)

- Low red cell count (RBC)

- High red distribution width (RDW)

- Normal or increased platelet count

A useful distinction between IDA and thalassaemia trait, which also presents with microcytic anaemia, is that the RBC and RDW is usually normal or slightly raised in cases of thalassaemia, despite the low MCV and MCH.

The reticulocyte count is usually normal or very slightly raised, unless the patient has been commenced on iron therapy. Commencement of iron therapy will restart erythropoiesis and cause reticulocytes to pour back into the circulation causing the reticulocytosis.

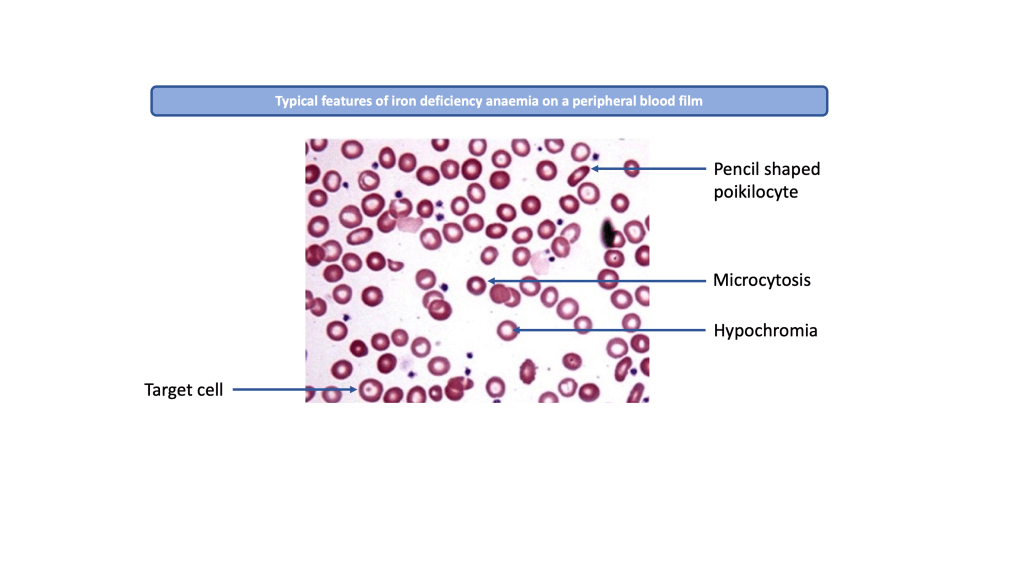

Peripheral blood film (PBF) examination will show small pale looking red cells with widened central pallor (hypochromic microcytic cells) or variable sizes and shapes (aniso-poikilocytosis). Normal red cells appear discoid but iron deficient cells show abnormal shapes such as pencil-shaped cells and target cells. Thrombocytosis may also be noted.

Biochemical investigations

A diagnosis of IDA should be confirmed by biochemical studies. Having understood the process of iron metabolism and regulation as outlined in the previous teaching module, it should be easy to predict what tests may be useful to confirm iron deficiency.

The tests used to assess iron status in the diagnostic laboratory and their typical findings in IDA are:

- Serum transferrin – increased

- Transferin saturation (TSAT) – reduced, less than 20%

- Serum total iron binding capacity (TIBC) – increased

- Serum ferritin – reduced, less than 20 ug/l

- Serum soluble transferin receptor (sTfR) – increased

Further investigations and basic management

Investigations

All patients with IDA should be investigated to identify the underlying cause for deficiency. Dietary history should be obtained. If a dietary cause has been excluded, the patient should be further investigated for potential chronic blood loss or malabsorbtion.

Important history that should be obtained include:

- In women, a menstrual history must be obtained as menorrhagia is often a cause of IDA.

- Gastrointestinal symptoms which may suggest peptic ulcer disease or a gastrointestinal malignancy.

- A drug history, particularly the use of NSAIDS and anti-platelet or anti-coagulant drugs

- Travel history suggesting potential parasitic infection

Investigations that should be considered based on the clinical history and physical examination may include:

- Urine analysis to identify haematuria and haemoglobinuria, which may occur with renal malignancies and chronic intravascular haemolysis (e.g. paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria)

- Faecal occult blood to identify gastrointestinal bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, haemangiomas and gastrointestinal malignancies

- Stool for ova and cyst to identify hookworm infestation

- Endoscopic examination which may include an oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGDS) or colonoscopy

- Coeliac screen (mainly in Western population)

Treatment

The underlying cause for IDA must be treated accordingly. Treatment of iron deficiency with iron therapy without identifying and treating the underlying cause is ill-advised as you may miss important serious conditions such as a malignancy.

Treatment of the iron deficiency can be achieved by using daily oral iron tablets which should be continued for at least 3 months after normalisation of the haemoglobin. This is to ensure that iron stores are fully replenished. Alternatively, intravenous iron can be used for patients who are non-compliant or intolerant to oral iron tablets.