Learning outcomes

- Relate disorders of globin change synthesis to the pathogenesis of thalassaemia and haemoglobin variants

- Describe the pathogenesis and clinical presentation of beta-thalassaemia

- Predict the risk of thalassaemia based on the genetic inheritance pattern of beta-thalassaemia

- List common molecular mutations associated with beta-thalassaemia in Malaysia

- Appraise the laboratory tests that are commonly used for screening and diagnosis of thalassaemia and haemoglobin variants

Prevalence

Beta-thalassaemia is a group of inherited disorders characterised by reduced or absent 𝜷-globin chain synthesis. Its global distribution resembles that of 𝜶-thalassaemia.

The prevalence is highest along Central, Southern and Eastern Asia, the Middle East as well as the north coast of Africa and South America. The highest frequencies are seen in Cyprus, Sardinia and Southeast Asia. In Malaysia, 4.5% of Chinese and Malays are estimated to be 𝜷-thalassaemia carriers. Among the Kadazandusuns of Sabah, prevalence is estimated at 12.8%.

Molecular basis of 𝜷-thalassaemia

In contrast to 𝜶-thalassaemia, the majority of mutations associated with 𝜷-thalassaemia are non-deletional. This means that the mutations either involve single nucleotides or short segments of nucleotides. Deletions of large spans across exons is uncommon in 𝜷-thalassaemia.

The 𝜷-thalassaemia mutations interfere with 𝜷-globin production, to either completely abolish the production (𝜷0) or reduce the output (𝜷+). Interference to 𝜷-globin chain synthesis may occur through;

- Inhibiting initiation of transcription by the 5′-promoter site

- Splice-site mutations that interfere with splicing of the exon from the intron at the exon-intron junction

- Start-site mutations that prevent initiation of translation

- Nonsense mutations and frame-shift mutations which abort translation

- Polyadenylation signal mutations in the 3′-UTR region of the mRNA that interferes with RNA processing

Over 300 different 𝜷-thalassaemia alleles have been described (http://globin.bx.psu.edu/hbvar), but only about 40 of them account for 90% of the 𝜷-thalassaemia worldwide.

Clinical and laboratory features

Beta thalassaemia may either present as;

- Heterozygous 𝜷-thalassaemia (𝜷-thalassaemia trait or carrier), when only a single allele is effected

- Homozygous 𝜷-thalassaemia, when both alleles are effected. The clinical presentation of homozygous 𝜷-thalassaemia may vary from thalassaemia intermedia to major, depending on the severity of the mutation causing disruption of 𝜷-globin production

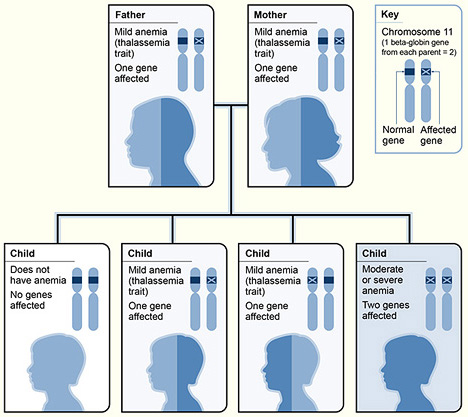

Children of heterozygous carrier parents have a 25% chance of being homozygous 𝜷-thalassaemia and 50% chance of being heterozygous carriers.

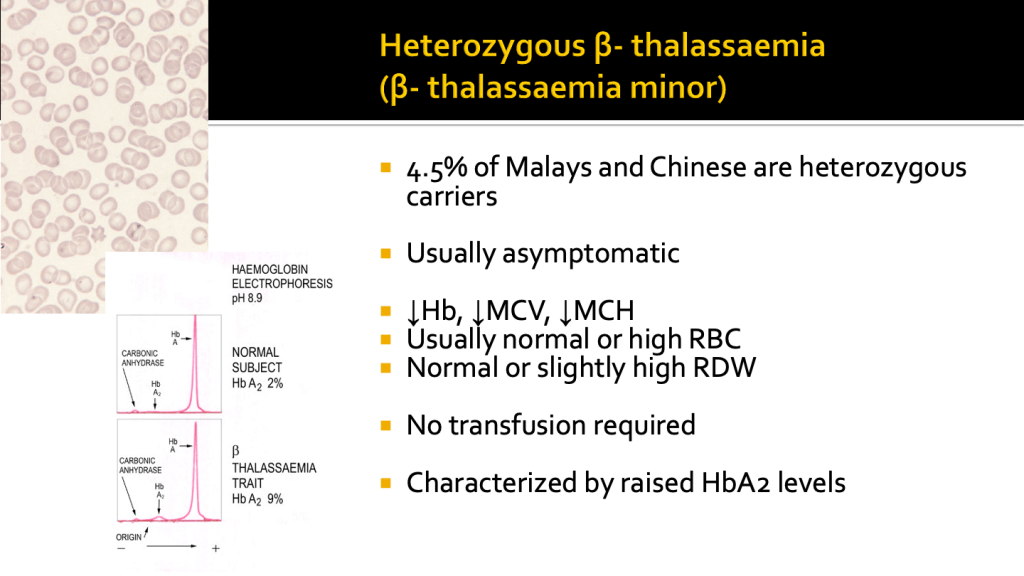

Heterozygous 𝜷-thalassaemia (𝜷-thalassaemia minor, trait or carrier)

Subjects with 𝜷-thalassaemia trait are clinically asymptomatic. They have mild anaemia with low MCV and MCH. Red cell count and RDW are usually within normal range. The peripheral blood film show hypochromic microcytic red cells and may be accompanied by some target cells.

Haemoglobin analysis characteristically shows an increase in HbA2 levels with normal HbF.

Homozygous 𝜷-thalassaemia (𝜷-thalassaemia major)

Subjects with both 𝜷-globin genes mutated, present with moderate to severe anaemia, depending on the type of mutations that they carry.

The clinical presentation of 𝜷-thalassaemia major usually occurs between 6 and 24 months, as the switch to HbA occurs in the infant. The baby shows failure to thrive and becomes progressively pale. Feeding problems and progressive enlargement of the abdomen caused by spleen and liver enlargement often occurs.

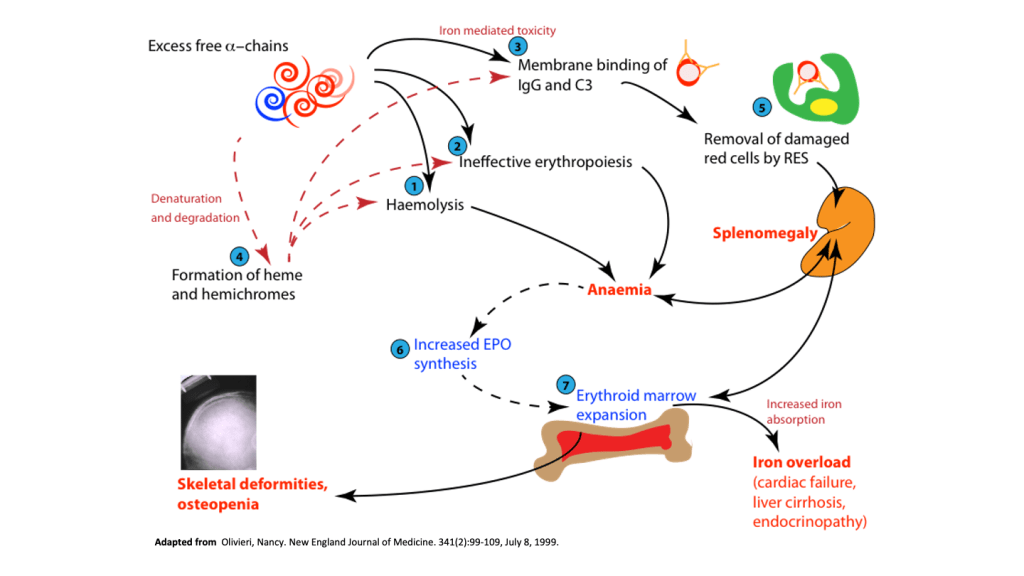

Failure to identify the condition early and institute transfusion therapy results in growth retardation, pallor and jaundice accompanied by massive hepatosplenomegaly. Other complications may include leg ulcers, development of masses from extramedullary hematopoiesis, and skeletal changes resulting from expansion of the bone marrow. Skeletal changes include deformities in the long bones of the legs and typical craniofacial changes with bossing of the skull and prominent malar eminence.

Excess of 𝜶-chains due to imbalance between 𝜶 and 𝜷-globin chain production, leads to the deposition of the 𝜶-globin chains within the red cells, leading to red cell membrane damage and destruction of the developing red cells with ineffective erythropoiesis.

Ineffective erythropoiesis resulting from red cell cell damage caused by the excess 𝜶-chains results in severe anaemia, with compensatory increase in serum erythropoietin levels driving marrow erythropoiesis.

Patients with 𝜷-thalassaemia major must be treated with effective red cell blood transfusions to maintain baseline haemoglobin at a level sufficient to inhibit the erythropoietic response. The general rationale for blood transfusion apart from maintaining haemoglobin levels for normal activity, is to suppress the patients own erythropoiesis so that marrow expansion and ineffective erythropoiesis does not proceed to cause more damage.

However, a major complication of blood transfusion is iron overload. This is due to the iron introduced through red cell transfusions that cannot be excreted, since iron has no excretory pathways. Patients with 𝜷-thalassaemia receiving regular blood transfusion also need to receive iron chelation therapy to prevent accumulation of iron and consequent iron damage from iron overload.

Iron overload

Iron is a highly toxic element due to its potential to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). Iron that is not bound to transferrin, or ferritin or to therapeutic iron chelators, generates a variety of reactive oxygen species (ROS), most notably hydroxyl radicals. Iron accumulation can cause;

- Lipid peroxidation from ROS generation with consequent cellular and DNA damage.

- Increased availability of iron to microorganisms thereby increasing the risk of infection.

The accumulation of iron occurs predominantly in the liver, heart and endocrine organs such as the pituitary, thyroid, parathyroid, pancreas, adrenals and testes. Major complications of iron overload in 𝜷-thalassaemia major include;

- Cardiac failure

- Liver cirrhosis and hepatoma

- Hypopituitarism and growth failure

- Hypothryroidism

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypogonadism

The complications of iron overload can be prevented by effective iron chelation therapy and close monitoring of the patient for early detection of complications and institution of interventions.

Splenectomy

Patients with 𝜷-thalassaemia major develop massive splenomegaly as a result of increased red cell clearance by macrophages and extra medullary erythropoiesis. Splenomegaly is further aggravated in the absence of appropriate effective red cell transfusion therapy.

Increasing spleen size contributes to hypersplenism and poor response to transfusion therapy. Patients with 𝜷-thalassaemia major therefore may need to undergo splenectomy when they show poor haemoglobin increments following red cell transfusions.

Children undergoing splenectomy however have an increased risk to infections, particularly from encapsulated bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria mengitidis and Haemophilus influenzae. They therefore should receive immunisation against the infections and penicillin prophylaxis.

Splenectomised patients also have a higher risk of thrombosis as platelet counts increase in the absence of a functioning spleen.