Learning outcomes

- Describe the life cycle of red cells

- Describe common clinical features associated with haemolysis

- Appraise tests that are useful in the evaluation of anaemia secondary to premature destruction of red cells

Red cell lifespan and end of life

The average red cell has a lifespan of about 120 days. During its lifetime, the red cell would have traveled approximately 500 km and circulated the body 170,000 times. The red cell leaves the marrow without a nucleus or mitochondria. The absence of a nucleus means that the red cell would not be able to transcribe any new proteins to replenish those that have been consumed during its journey. In addition, the red cells cannot generate new ATP molecules for energy through oxidative phosphorylation, as this process occurs in the mitochondria.

As they course through the circulation, red cells are exposed to to oxygen radicals, toxins, microbes and antibodies. They have to undergo multiple deformations in order to squeeze through capillaries.

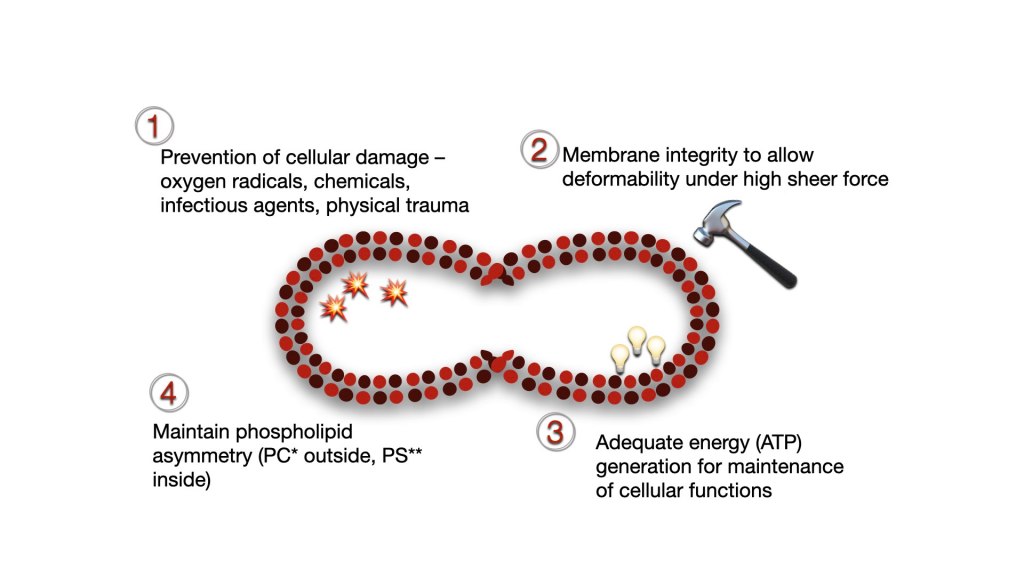

Red cells have evolved to withstand the various challenges while they circulate and perform their function. Red cell integrity is ensure through:

- Surface and cellular contents designed to prevent cellular damage from oxygen radicles, chemical, infectious agents, complements and physical trauma

- Membrane structure that can deform without rupturing under high sheer force

- Adequate ATP generation to maintain cellular processes throughout life

- Maintenance of phospholipid asymmetry, with phosphotidylcholine (PC) on the external surface and phophatidylserine on the inner surface.

At the end of its lifespan, senescent red cells are recognised by splenic macrophages and destroyed by phagocytosis. Heme is degraded following phagocytosis and the iron recycled and returned to circulation.

Pathophysiology of haemolysis

Haemolysis is the process of destruction of cells and is a natural end to red cells. However, excessive or early haemolysis before the natural end of a red cell, will result in haemolytic anaemia. The anaemia may be compensated by increased erythropoiesis (compensated haemolytic anaemia) up to a point when red cell production is unable to keep up with red cell destruction.

The majority of red cells are destroyed in the extra-vascular space following phagocytosis by macrophages within the spleen. This form of haemolysis is called ‘extra-vascular haemolysis‘, as the breakdown of cells occur within macrophages and not in the circulation.

Haemolysis within the circulation or ‘intra-vascular haemolysis‘ does not occur physiologically but can be precipitated in some pathological conditions (e.g. autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, G6PD deficiency, sepsis).

Extra-vascular haemolysis

In extra-vascular haemolysis, red cells are phagocytosed by macrophages at the end of their life-cycle. Extra-vascular haemolysis can also occur in many pathological conditions where the red cells are mis-formed (e.g. red cell membrane defects, enzyme defects, thalassaemias) or if they are coated by antibodies or opsonised (e.g. immune haemolytic anaemia).

Following phagocytosis, red cell haemoglobin is released within the phagosome, and separated into its component parts – globin and heme. The globin peptide is degraded into amino acids by proteosomes. The heme component is meanwhile cleaved by the enzyme heme oxygenase into iron (Fe2+), biliverdin and carbon monoxide.

The green pigmented water-soluble biliverdin is reduced to the yellow pigmented water-insoluble bilirubin, which passes into circulation bound by albumin (unconjugated bilirubin). Bilirubin bound to albumin is transported to the liver, where is is conjugated with glucoronic acid by UDP-glucoronyl transferase to bilirubin diglucoronide (which is commonly called conjugated bilirubin).

Conjugated bilirubin is excreted from the hepatocyte into the biliary tract, where it passes into the intestines. Gut bacteria convert the bilirubin to urobilinogen. Urobilinogen produced by the gut bacteria have several routes:

- Oxidation to the brown pigment, urobilin , which can be excreted in faeces as stercobilin and gives faeces its characteristic colour

- Reabsorption in the small intestine and recirculation back to the liver, forming an entero-hepatic circulation

- Reabsorption into blood and passage to kidney for excretion in urine

Based on the above physiology, it can be inferred that excessive haemolysis will result in:

- Increased uncojugated bilirubin when UDP-glucoronyl transferase activity is not sufficient to conjugate the increased amounts of bilirubin delivered to the hepatocytes, as a consequence of increased red cell breakdown.

- Increased urobilinogen in urine (urobilirubinuria) due to increased reabsorption of urobilinogen from the gut and excretion by the kidney.

- Increased faecal stercobilin due to excretion of the oxidised urobilin produced in the gut.

Intravascular haemolysis

Rupture of red cells directly in the blood vessel without being engulfed by macrophages is termed as intravascular haemolysis. Once ruptured, the red cell contents spill into the circulation. Free haemoglobin and iron is toxic to the body and must be removed to prevent damage to endothelium and organs as a result of oxidative damage from reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide disregulation.

Three routes are available to clear free haemoglobin from circulation:

- The tetrameric haemoglobin (Hb) is split into dimers and bound to haptoglobin (Hp). The Hb-Hp complex is taken up by macrophages, mainly in the spleen. The heme can therefore be degraded to bilirubin and the iron reutilised. This process prevents oxidative damage to tissues from the iron in free plasma haemoglobin or loss of iron through the kidneys that can cause renal damage.

- Free Hb can oxidise to met-haemoglobin (metHb) which contains Fe3+ instead of Fe2+. The heme molecule containing Fe3+ (met-heme) can dissociate from globin and be bound to haemopexin. The met-heme-haemopexin complex is then taken up by macrophages mainly in the spleen for degradation to bilirubin and reutilisation of iron. Excess met-heme can also bind to albumin to form met-heme-albumin.

- Free haemoglobin appears in urine (haemoglobinuria) once both of the above routes are saturated i.e. haptoglobin and haemopexin is depleted. In chronic intravascular haemolysis, haemoglobin in the urine may be reabsorbed in the proximal convoluted tubules and the iron portion removed and stored as haemosiderin. Hemosiderin may therefore appear in the urine (hemosiderinuria).

Intravascular haemolysis is therefore associated with:

- Decreased haptoglobin and haemopexin

- Increased met-heme-albumin (which is shown by a positive Schumm’s test)

- Haemoglobinuria (note the difference from haematuria, which is presence of red cells in urine, and not a feature of intravascular haemolysis)

- Haemosiderinuria in chronic intravascular haemolysis

Clinical features

Haemolytic anaemias are usually characterised clinically by the triad of pallor, jaundice and splenomegaly.

Anaemia develops once the marrow output is unable to keep pace with the rate of red cell destruction. Many patients with chronic haemolytic anaemia do not show signs of symptoms of anaemia as their body have compensated for the increased red cell destruction by increasing erythropoiesis and cardiac output. Acute haemolysis such as that precipitated through drugs, infections, autoimmune and alloimmune causes however may be severe and life threatening. The general features associated with anaemia described before is also applicable to haemolytic anaemia.

Jaundice is observed clinically due to accumulation of bilirubin which is predominantly unconjugated. Patients with significant intravascular haemolysis secondary to drugs, infections or immune causes may pass dark urine due to haemoglobinuria.

Splenomegaly may be observed in patients with chronic haemolysis. It is often a characteristic finding in red cell membrane disorders such as spherocytosis and enzyme disorders disorders such as pyruvate kinase deficiency. Many clinically significant forms of thalassaemia will present with splenomegaly. Mild splenomegaly may also be seen with some autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. The splenomegaly in haemolytic anaemia occurs due to congestion of the spleen and macrophage hyperactivity.

Some patients with chronic haemolysis may also develop pigment gallstones due to the high concentration of bilirubin that is secreted into the biliary system and collects in the gallbladder.

Folate deficiency and megaloblastic anaemia may also occur if there is inadequate folate to support the increased erythropoiesis that occurs to compensate for the haemolysis. Folate supplementation is usually necessary for patients who have chronic haemolysis.

Laboratory features

The laboratory features observed with haemolytic anaemia can generally be attributed to two main pathological processes.

Increased haemoglobin breakdown

- Hyperbilirubinaemia, predominantly unconjugated

- Reduced plasma haptoglobin and haemopexin

- Increased plasma lactate dehydrogenase

- Increased urinary urobilinogen (urobilirubinuria)

- Haemoglobinaemia*

- Methaemalbuminaemia*

- Haemosiderinuria*

*usually observed with intravascular haemolysis

Compensatory erythroid hyperplasia

- Reticulocytosis

- Erythroid hyperplasia of bone marrow