Learning outcomes

- Explain the biochemistry of B12 in relation to the pathogenesis of megaloblastic anaemia

- Describe the absorption and transport of B12

- List the causes of B12 deficiency

- Describe unique clinical features associated with B12 deficiency

Biochemistry

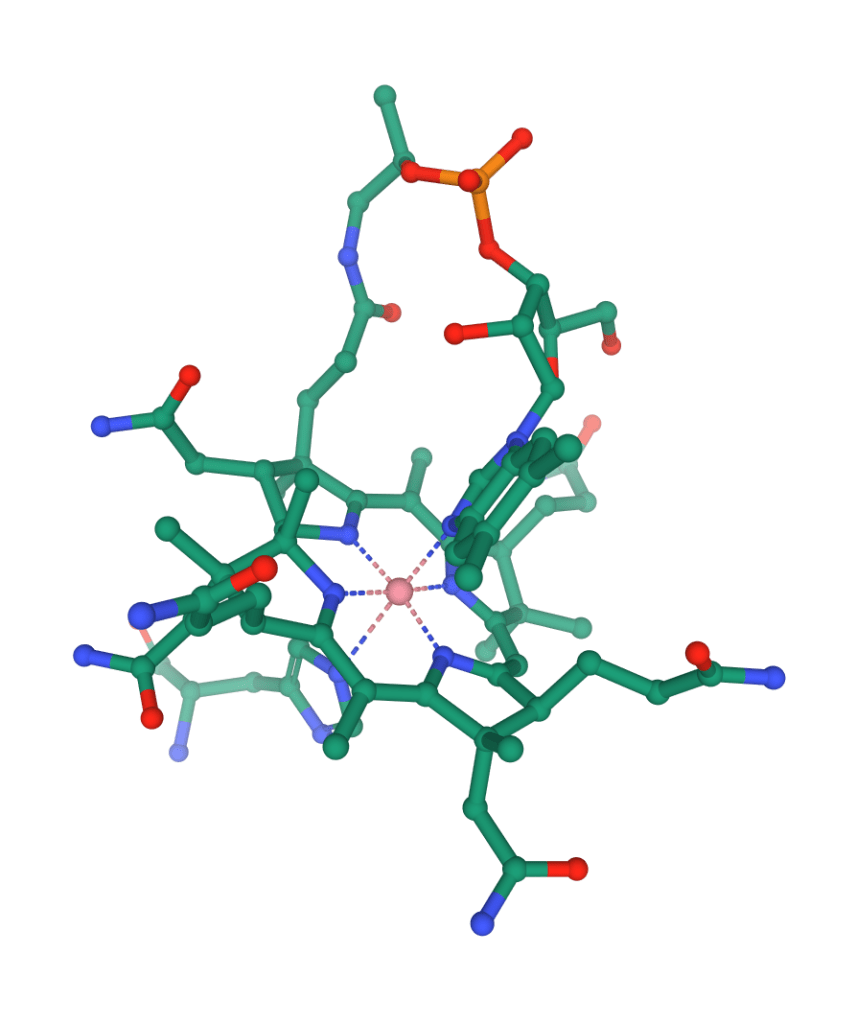

Vitamin B12 or cobalamin is a water soluble vitamin that is essential for cell function. It is the largest and most structurally complex of all vitamins and is characterised by a porphyrin-like corrin ring nucleus that contains a cobalt atom bound to a dimethyl benzimidazole nucleotide.

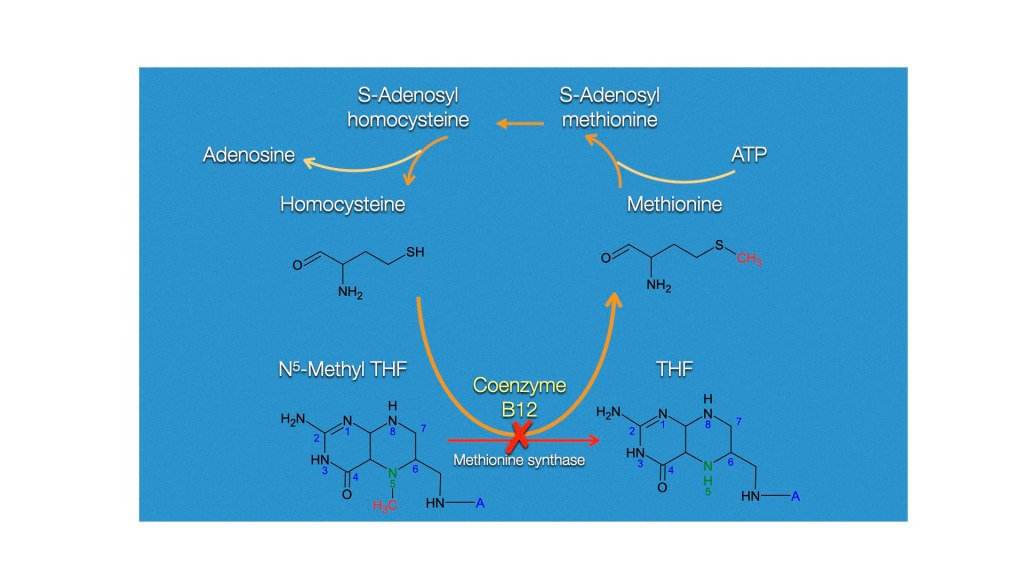

Vitamin B12 functions as a cofactor for methionine synthase and L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase.

Methionine synthase

As mentioned earlier in the context of folate metabolism, methionine synthase catalyses the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine is required for the formation of S-adenosylmethionine, a universal methyl donor for almost 100 different substrates, including DNA, RNA, hormones, proteins, and lipids.

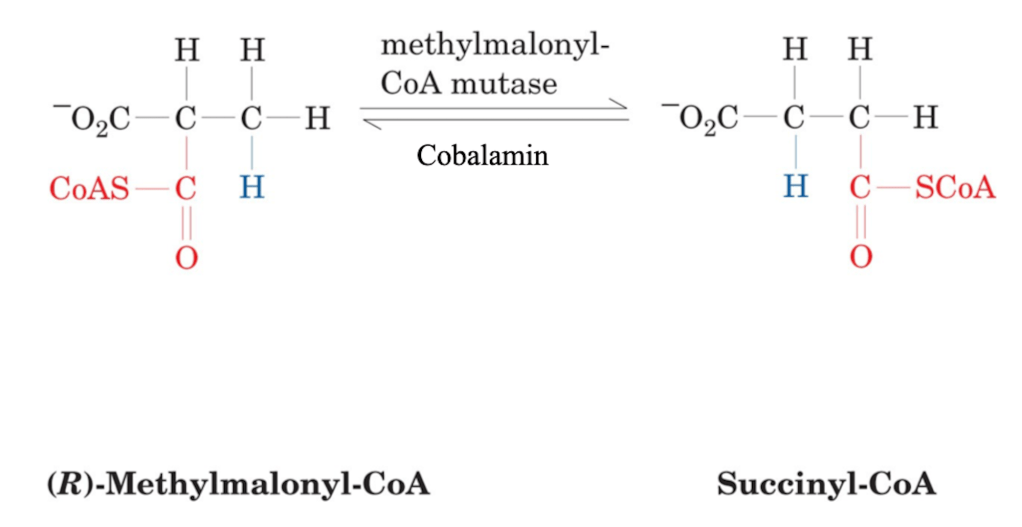

Methyl-malonyl CoA mutase

Cobalamin also acts as a co-factor to L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, which converts L-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA in the degradation of propionate, an essential biochemical reaction in fat and protein metabolism. Succinyl-CoA is also required for hemoglobin synthesis.

Vitamin B12 absorption and distribution

Dietary source and requirements

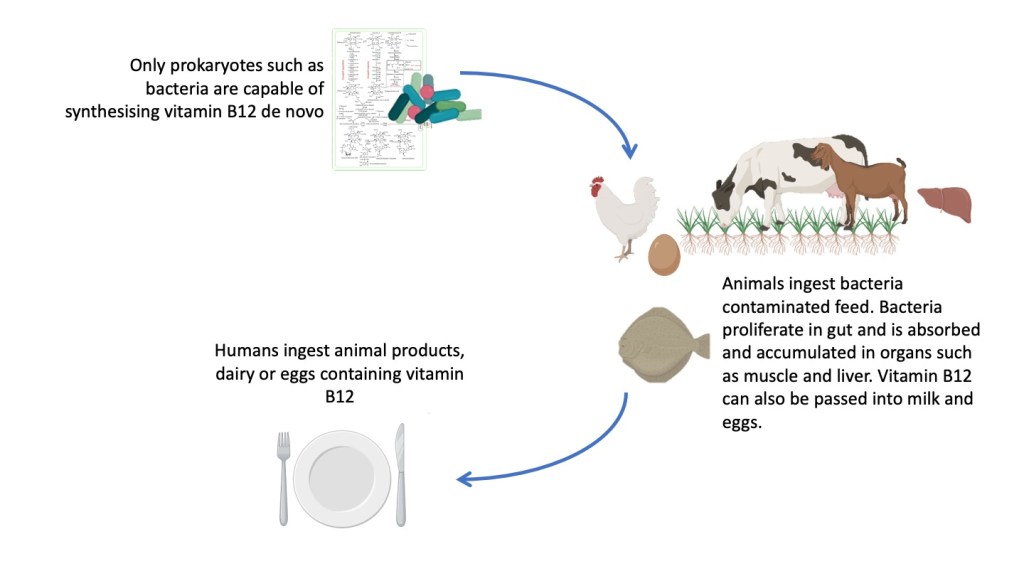

The only organism capable of synthesising vitamin B12 are prokaryotes such as bacteria. Animals take up the bacteria when they eat plants contaminated by bacteria, which then enter the animal’s digestive system, forming part of their permanent gut flora, hence forming vitamin B12 internally. Animals also store the vitamin B12 that is absorbed in their liver and muscle as well as pass it to their egg and milk.

Humans acquire vitamin B12 by eating animal products and fermented food. Vitamin B12 forming bacteria form part of the normal human gut flora but these are usually found in the large intestine and is not absorbed. Humans therefore depend on their diet as a source of vitamin B12.

Sources of vitamin B12 include fish, meat, poultry, eggs, milk, and milk products. Plants are a negligible source of vitamin B12, hence vegans are at high risk of developing vitamin B12 deficiency. Fermented products of non-animal source such as tempeh and marmite may be an alternate source of vitamin B12 for vegans.

The daily requirements of vitamin B12 in an adult is about 2 𝝻g. Pregnant and lactating women will require higher intakes. The total body B12 stores are approximately 2-5 mg and is stored mainly in the liver. Considering that total body B12 stores is more than 1,000 times of daily requirements, it is estimated that 2-3 years need to pass before an individual shows evidence of vitamin B12 deficiency once B12 intake is terminated (e.g. veganism, gastrectomy).

Absorption

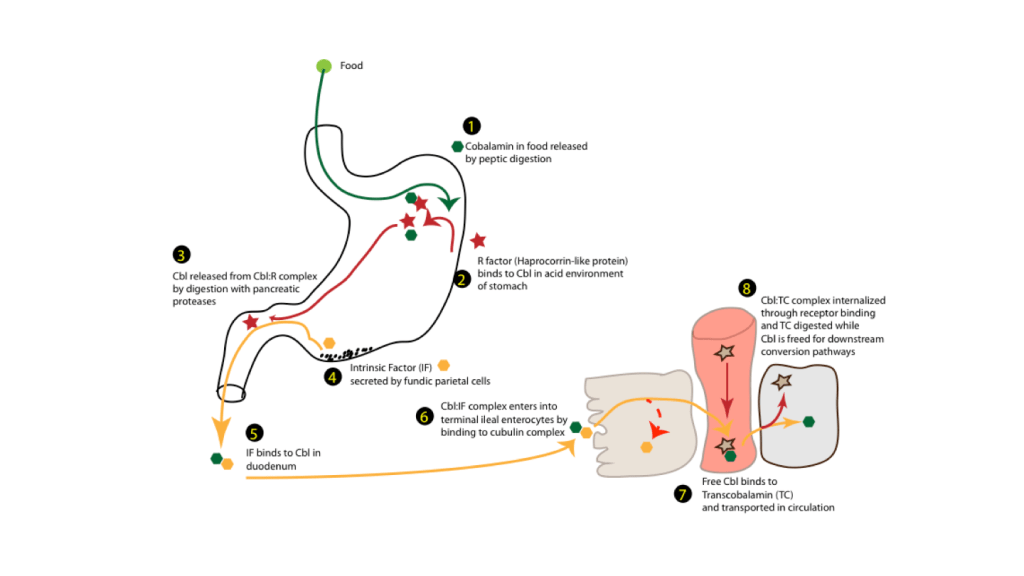

Vitamin B12 is absorbed in the ileum. However, its intake by the enterocytes is dependant on the low pH of the stomach and functioning parietal cells that produce intrinsic factor (IF).

Proteolytic digestion of ingested food by pepsin occurs within the acidic environment of the stomach, releasing cobalamin from the food. Once released, cobalamin binds to haptocorrin (R-protein), a high-affinity cobalamin-binding protein found in the saliva and gastric juice, forming a “holo-R-protein” complex.

In the second part of the duodenum, pancreatic proteases degrade the holo-R-protein complex, and the resulting free cobalamin binds to IF secreted by the parietal cells of the stomach. The cobalamin-IF complex is stable and resistant to proteolysis in pH ranges of 3 to 9.

Ileal IF-cobalamin receptors are selective for IF-bound cobalamin and not for R-bound cobalamin; thus, ileal pancreatic proteases are necessary as much as gastric peptic proteases to ensure optimal cobalamin absorption. IF secretion parallels the secretion of gastric acid, being stimulated by food and inhibited by H2 blockers, as well as by proton pump inhibitors. Long-term use of these two classes of drugs may lead to food-cobalamin malabsorption.

The final step of cobalamin absorption takes place in the ileum through specific membrane-associated IF-cobalamin receptors on the enterocytes. Absorbed cobalamin is transported in circulation by transcobalamin-II (TC-II).

Causes of vitamin B12 deficiency

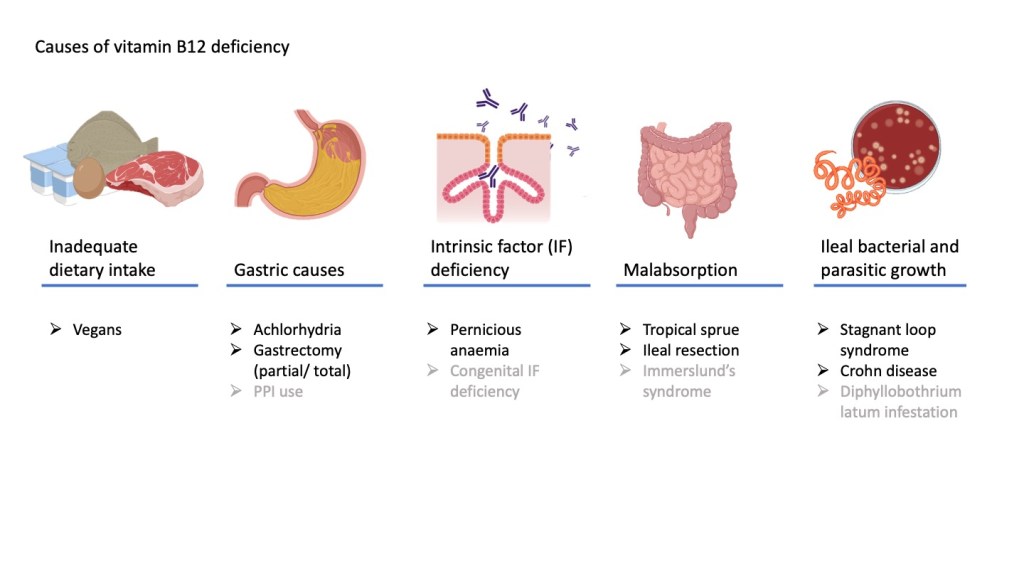

Vitamin B12 due to dietary insufficiency is rare except in strict vegans who do not consume any meat, dairy products or eggs.

Because vitamin B12 is dependant on gastric acidity, pepsin digestion and IF production by the gastric parietal cells. it is no wonder that gastrectomy and conditions that reduce gastric acidity such as atrophic gastritis and chronic proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use may contribute to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Pernicious anaemia due to auto-antibodies directed against parietal cell or IF is seen among Northern Europeans and has a familial association. There may be association with other autoimmune conditions such as thyroid disorders (primary hypothyroidism, Hashimoto thyroiditis, thyrotoxicosis), Addison disease, premature greying hair, vitiligo and hypoparathyroidism. Females are more commonly affected. Patients with pernicious anaemia have a higher risk of gastric carcinoma.

Within the ileum, conditions that predispose to small intestine bacterial overgrowth contribute to vitamin B12 deficiency as the bacteria competes for absorption of vitamin B12. This can occur following congenital or acquire malformations (e.g. oleo-colic fistula, anatomical blind loop, jejunal diverticulosis, strictures, Crohn disease). Surgical resection of the ileum also predispose to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Dhyphyllobothrum latum is a broad tapeworm native to Scandinavia, western Russia, and the Baltics. Ingestion of contaminated undercooked seafood may cause infestation in humans and competition with the parasite for vitamin B12.

Rare congenital deficiencies of proteins involved in vitamin B12 absorption (Imerslund-Grasbeck syndrome) and transport (TCII deficiency) may present as megaloblastic anaemia in childhood.

Clinical features

The clinical features associated with the megaloblastic anaemia of vitamin B12 deficiency is indistinguishable from folate deficiency. Patients present with signs and symptoms associated with anaemia and on examination, may show glossitis and angular stomatitis. Mild jaundice may occur due to the underlying dyserythropoietic anaemia and destruction of erythroid precursors in the marrow.

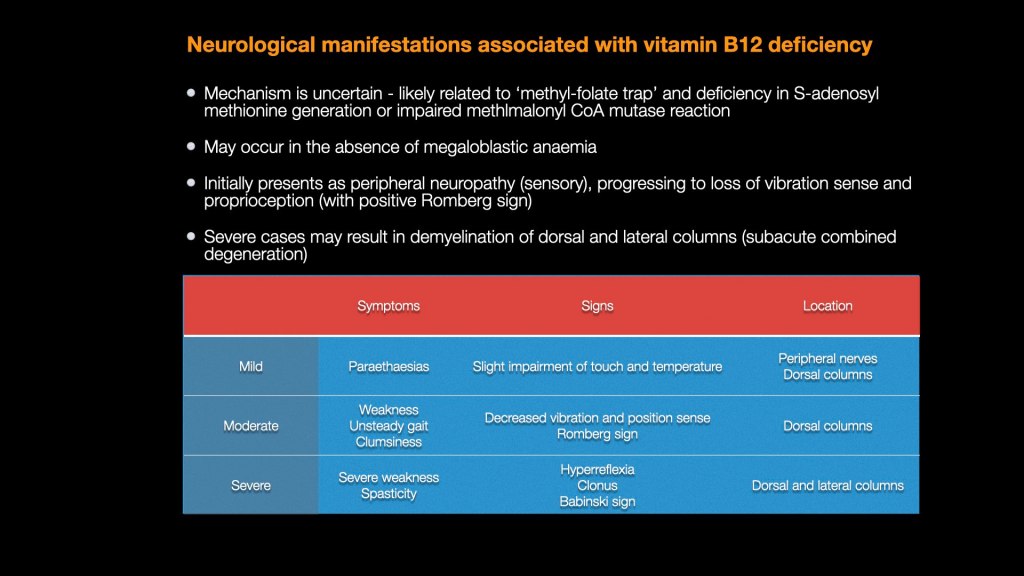

Of great importance though, vitamin B12 deficiency can present or be complicated by neurological symptoms. This is in contrast with folate deficiency which is not associated with neurological deficits. On the contrary, neurological deficits due to vitamin B12 deficiency can appear or be worsened if treated with folate solely.

Laboratory features

The full blood count and peripheral blood film will show features of megaloblastic anaemia, indistinguishable from that seen with folate deficiency.

Serum vitamin B12 levels will be reduced with normal serum folate levels. Holo-transcobalamin which measures the active vitamin B12 transported in circulation by TCII will also be reduced.

Homocysteine will be increased, similar as seen in folate deficiency. However, methyl malonyl-CoA will also be increased unlike in folate deficiency, as vitamin B12 is the only co-factor in methyl malonyl-CoA mutase activity.

Further investigations and treatment

Patients suspected to have pernicious anaemia should have gastroscopy and biopsy performed which will show evidence of autoimmune gastric atrophy. Autoantibodies of parietal cells or intrinsic factor may be demonstrated.

Treatment usually involves administration of hydroxycobalamin 1000 ug, given intramuscular daily for 1 week to restore the blood picture to normal and replenish B12 body stores, A maintenance dose of 1000 ug every 2 – 3 months may be required in patients where the B12 deficiency cannot be remedied (e.g. gastrectomy, ileal resection)