- Learning outcomes

- Normal fluid homeostasis

- Causes of oedema

- Clinical features of oedema

- Cor pulmonale

- Pulmonary oedema

- Congestion

Learning outcomes

Basic physiology

- Describe the normal distribution of water within the various fluid compartments of the human body

- Explain how the distribution of water is maintained through the balance of hydrostatic and oncotic forces at the capillary bed (Starling forces)

Pathophysiology of oedema

- Define oedema

- Explain how disturbances in balance of the hydrostatic and oncotic forces result in oedema

- Classify the general causes of oedema and list common examples for each of the cause

- Outline the pathophysiology, clinical and histopathological features that occur in various organs as a result of oedema

- Differentiate the pathophysiology and causes of pulmonary oedema from oedema that is generalised or localised to systemic organs

- Explain the term congestion and its relationship to oedema

Normal fluid homeostasis

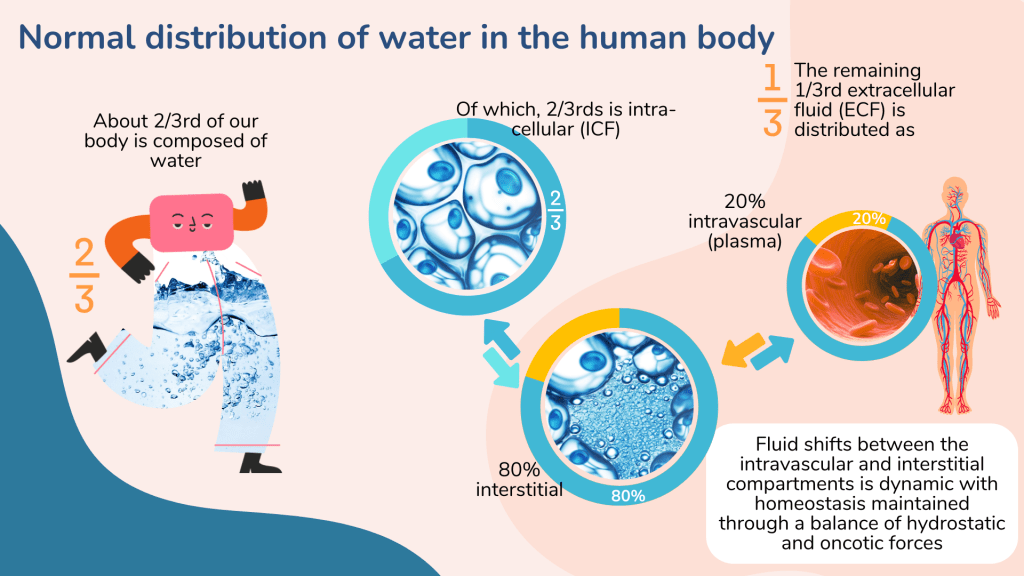

About 2/3rds of the total body weight is composed of water. The water content may vary according to age, sex (adult male ~ 60%, female ~ 55%) and muscle mass. Infants have higher water content (~80%) and elderly lower content (50 – 55%).

The total body water is distributed as intracellular (ICF) and extracellular fluids (ECF). Within the ECF compartment, water is divided between the intravascular and interstitial spaces. About 80% of the ECF is within the interstitial space while another 20% exists in the intravascular space as blood plasma.

There is fluid shifts between the intracellular, interstitial and intravascular spaces which is principally determined by two opposing forces – hydrostatic and oncotic force.

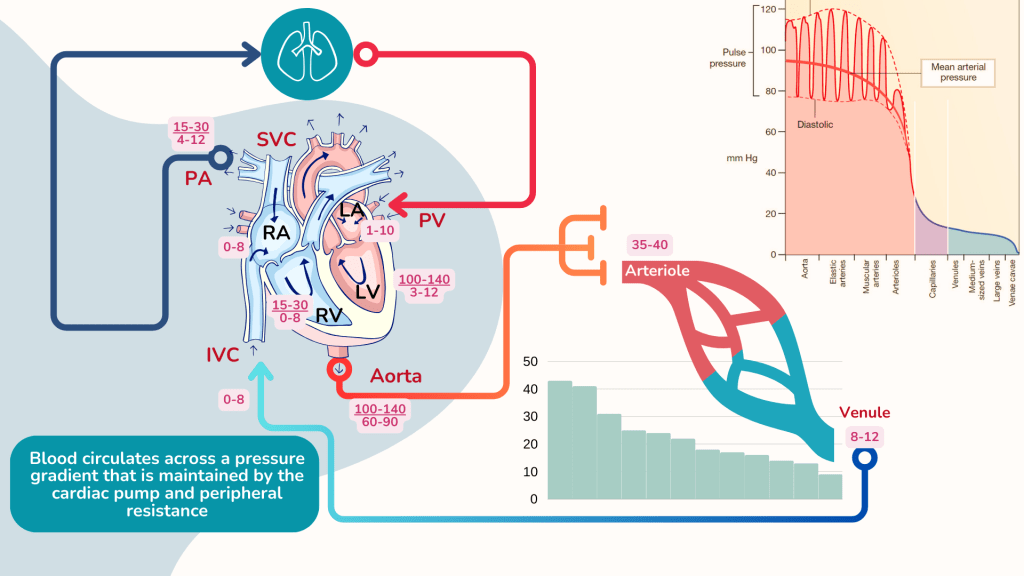

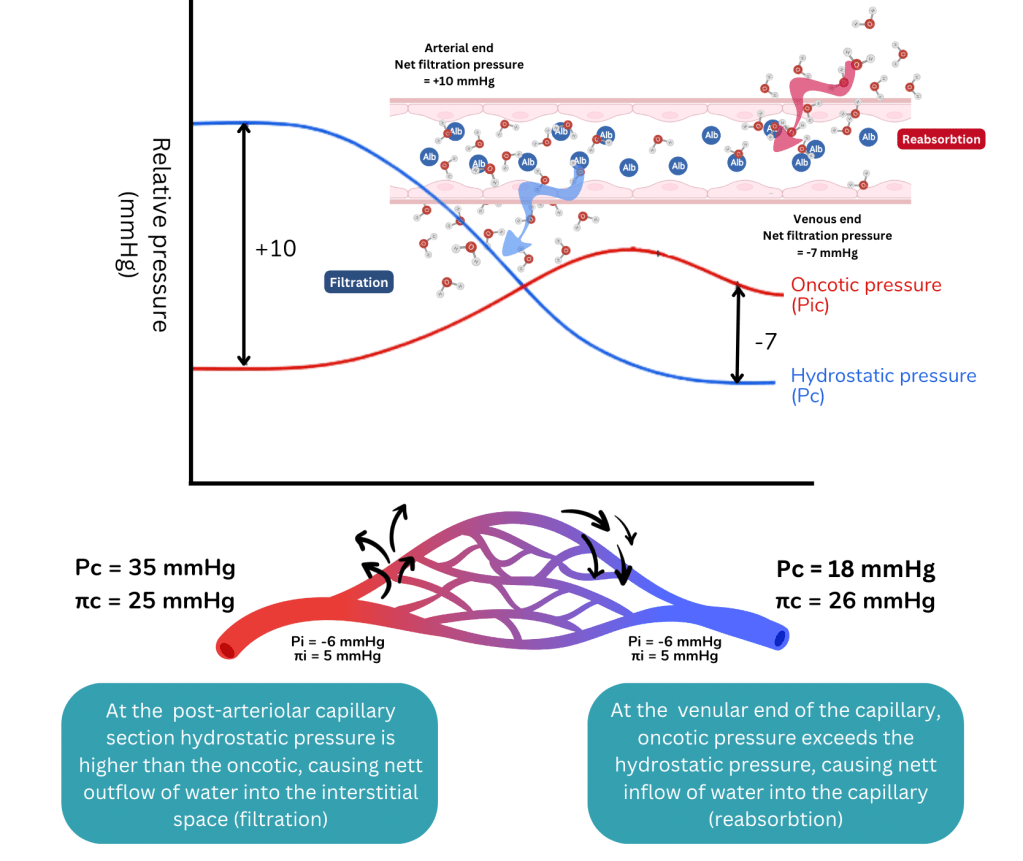

Hydrostatic pressure

Capillary hydrostatic pressure is basically the blood pressure at the level of the capillary. Blood leaves the heart and travels through the arteries along a pressure gradient and by the time it arrives at the arteriolar end of the capillary, the pressure is about 35-40 mmHg. The pressure declines further as it passes through the capillaries to the venule.

Oncotic pressure

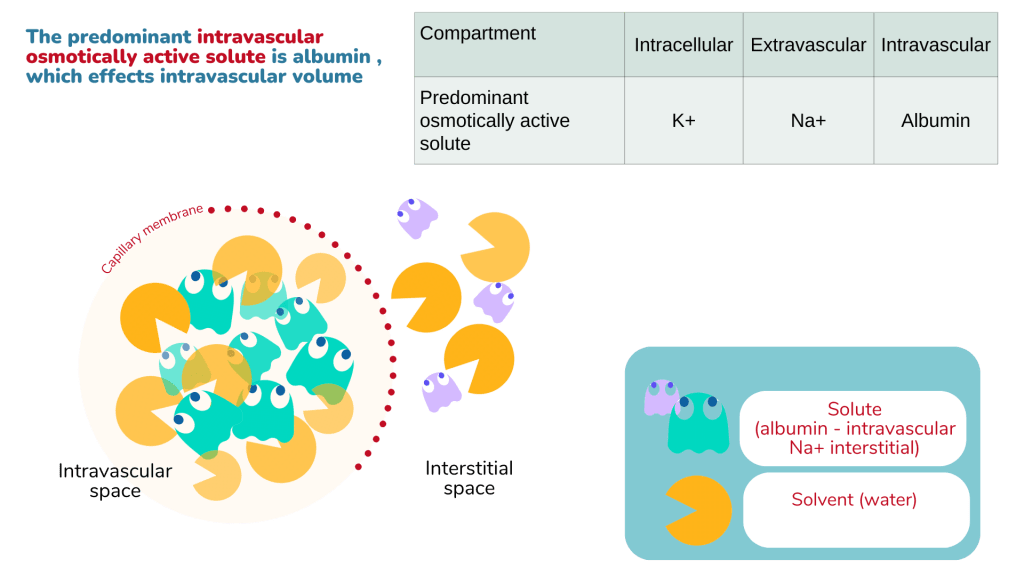

Capillary oncotic pressure is the osmotic pressure generated by large molecules especially proteins such as albumin in plasma. The intravascular oncotic pressure exerted by plasma is about 25 mmHg, and does not normally vary significantly with location in the body because the plasma is regulated and it mixes rapidly. There may be a slight increase in osmotic pressure at the venular end of capillaries as compared to the arteriolar end due to haemoconcentration as fluid exits the capillary, but this difference is negligible.

May the forces be with you … Starling hypotheses

The balance of the hydrostatic and oncotic pressures within the capillary and the interstitial compartments determine how fluids move across the semi-permeable membrane of the capillaries.

At the arteriolar end of the capillary, intra-capillary hydrostatic pressure exceeds the osmotic pressure, therefore forcing fluid to move out of the capillary, forming the filtrate.

By the time, blood arrives at the venular end, the hydrostatic pressure would have reduced across the pressure gradient. The balance of forces shift with osmotic pressure exceeding the hydrostatic pressure, and therefore fluids can be reabsorbed into the capillary.

It should be emphasised that the shifts in fluid is a dynamic process and the net capillary filtration rate is determined by local conditions, with the opposing actions of hydrostatic and oncotic forces within and outside the capillaries as explained by Starling’s hypotheses.

The opposing hydrostatic and oncotic forces in the capillary and interstitium determines the net capillary filtration rate i.e. the rate at which fluids move out of the capillary into the interstitial compartment.

It is also generally understood now that the traditional Starling relationships is invalid when applied to many systems (ref). Nonetheless, it is important to understand the basic concepts, as it provides a simple explanation on how pathophysiological disturbances contribute to development of oedema.

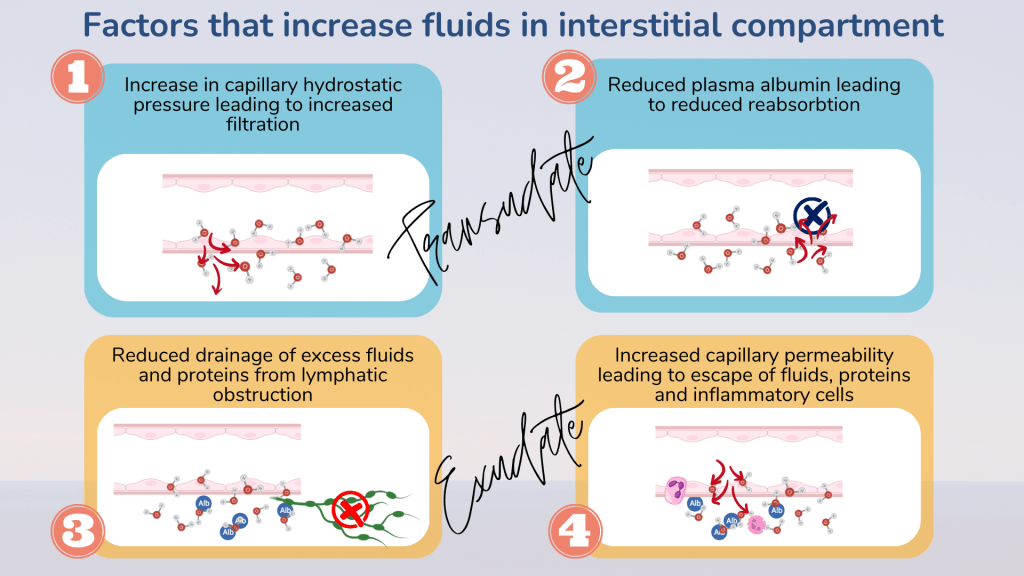

Any imbalance in the forces causing excessive net fluid movement out of the capillary into the interstitial compartment results in oedema. Oedema is therefore defined as the abnormal accumulation of fluids in the interstitial tissue spaces and body cavities.

Causes of oedema

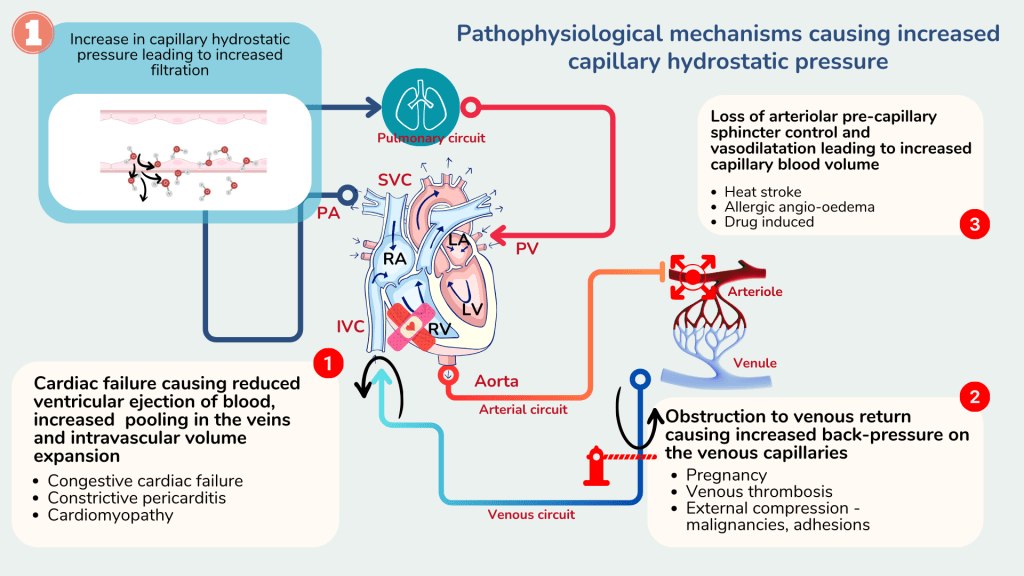

1. Increased hydrostatic pressure

Increased hydrostatic pressure within the capillaries causes excessive net movement of fluids from the capillaries into the interstitial compartment. This causes fluid to accumulate in the interstitial space causing oedema.

An increase in hydrostatic pressure commonly occurs due to two factors.

- Impaired venous return due to impaired cardiac function e.g. congestive cardiac failure, constructive pericarditis, cardiomyopathy

- Venous obstruction, either from the outside e.g. malignancy, pregnancy, liver cirrhosis or within the lumen e.g. venous thrombus.

Rarely, oedema may occur following an increase in capillary blood volume that occurs with loss of arteriolar pre-capillary sphincter control such as in heat stroke, allergic angio-oedema or drug reactions.

Impaired venous return or venous obstruction causes blood to accumulate in the veins proximal to the right ventricle or the site of obstruction. The collected blood pools and exerts increased hydrostatic pressure, similar to a blocked pipe. Based on the Starling equation, when the hydrostatic pressure increases, net filtration rate increases and therefore more fluid moves out of the capillary and accumulates in the interstitial space causing oedema.

Capillary hydrostatic pressure may also be further increased when there is compensatory increase in circulating blood volume. This may occur in cardiac failure and renal impairment. Reduced renal perfusion either due to decreased cardiac output or impaired renal function causes activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway and renal sympathetic activity. This causes expansion of the intravascular blood volume that can contribute to oedema.

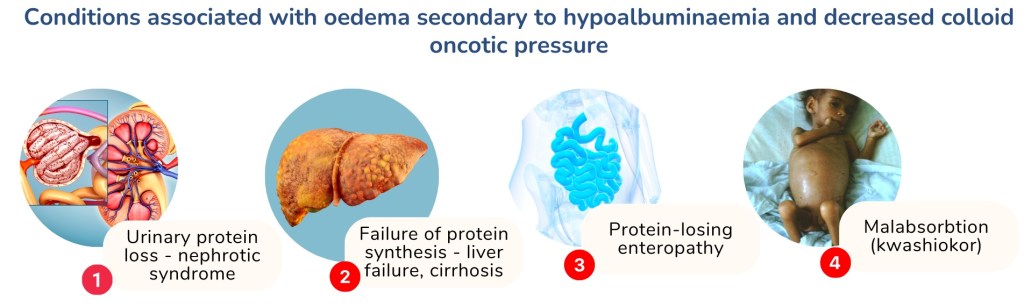

2. Reduced oncotic pressure

Intravascular oncotic pressure is mainly contributed by plasma albumin. Therefore, conditions that cause low plasma albumin i.e. hypoalbuminaemia can result in net filtration increase, as there is not enough colloid oncotic pressure to reabsorb fluid into the circulation.

Common conditions associated with hypoalbuminaemia include urinary protein loss such as seen in nephrotic syndrome and failure of protein synthesis as in liver failure and liver cirrhosis. Less common conditions include protein-losing enteropathies associated with malabsorption syndrome and protein malnutrition as in kwashiorkor.

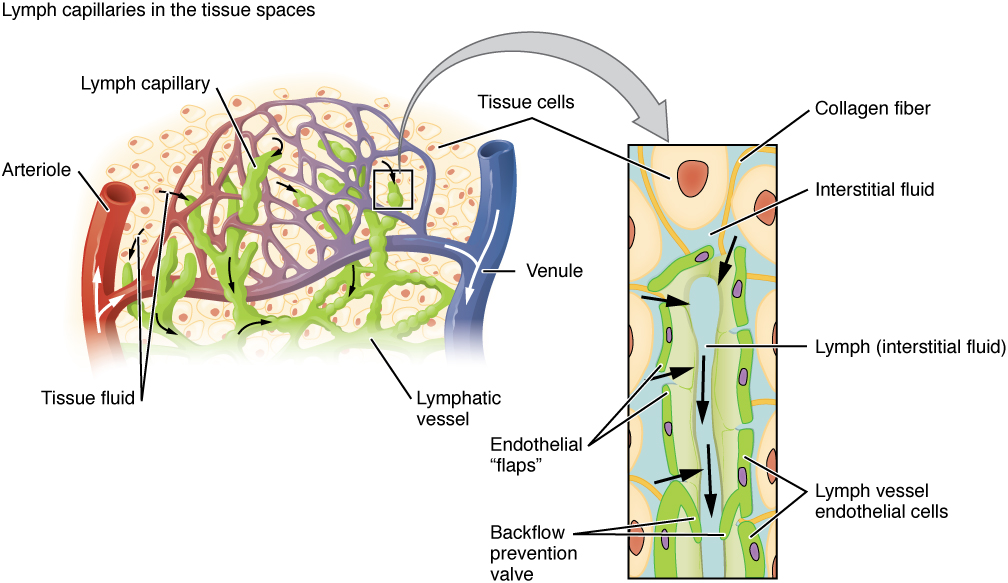

3. Lymphatic obstruction

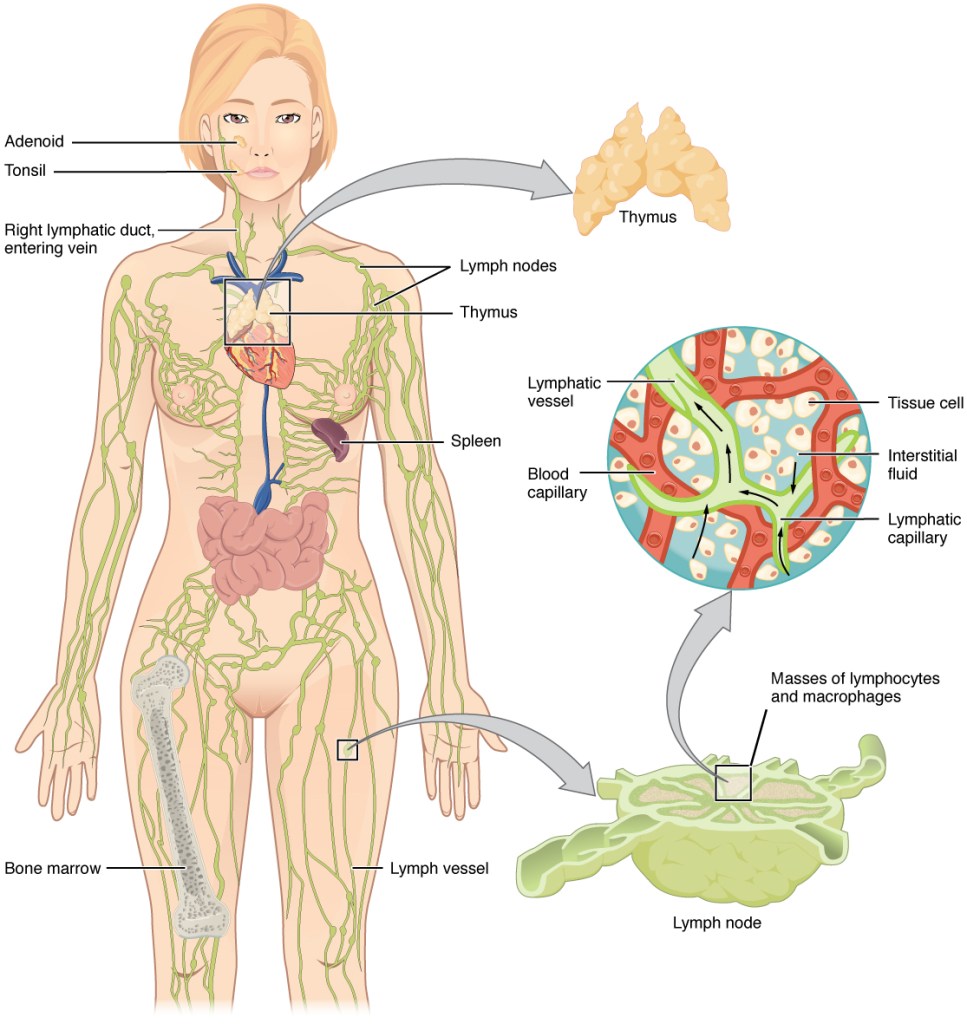

The lymphatics removes excessive fluid from the interstitial compartment. The collected fluid is returned to the circulation where it drains into the thoracic duct.

Organization of the lymphatic vascular tree and its role in drainage of fluids from the interstitial space into the lymphatic duct (OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons, OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Lymphatic obstruction causes failure of interstitial fluid drainage, somewhat like getting your house flooded because the drains are blocked. The lymphatics may be obstructed due to external compression from a tumour or following damage to its structure from surgery, radiation or injury. Filariasis, a parasite which lives in the lymphatics can also obstruction and localised oedema.

The oedema fluid in lymphoedema is however protein rich and contains various cellular debris as the obstructed lymphatics impair drainage of not only water but other waste material that escapes the capillaries. This is in contrast to oedema that occurs due to increased hydrostatic pressure or reduced oncotic pressure, where the interstitial fluid is composed of water forming a transudate.

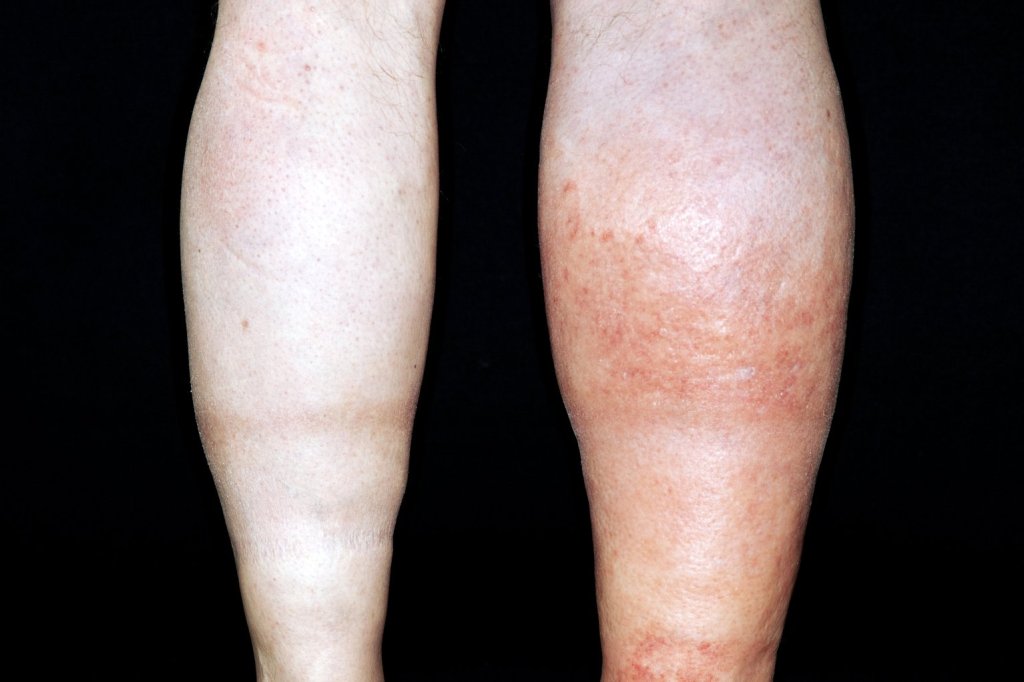

Clinical features of oedema

Oedema can be localised or generalised, depending on its pathology. Gravity plays an important role in distributing the accumulated fluid, with the lower limbs particularly prone to fluid accumulation on standing, which is known as dependant oedema. The accumulated fluid in the interstitial space causes distension of the skin which is evident in the extremities and where skin is lax, such as around the eye in the face, giving rise to facial puffiness.

Periorbital oedema and facial puffiness due to superior vena cava obstruction from an intrathoracic tumour (Dermatology Online Reports)

The accumulated fluids may also be retained in the body cavities causing abdominal distension with ascites, pleural and pericardial effusion.

Cor pulmonale

Cor pulmonale is a condition in which there is diminished right ventricular function with cardiac dilatation, caused by a primary dysfunction of the lung that leads to pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary hypertension can be associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease, autoimmune disorders or be idiopathic.

The consequent impairment in right ventricular function and diminished venous return leads to backlog of blood, increased venous hydrostatic pressure and the characteristic findings of hepatomegaly, ascites and generalised oedema.

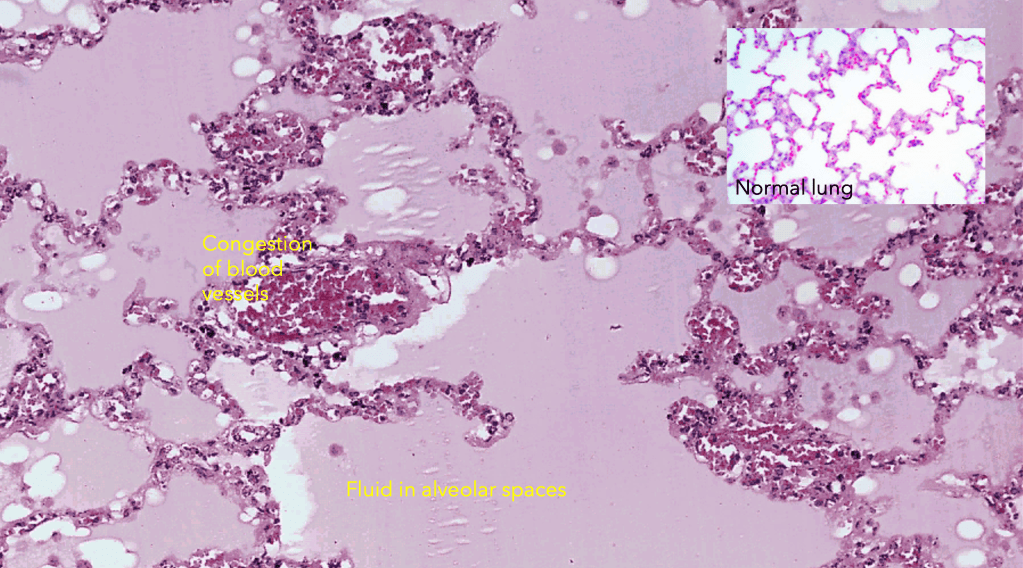

Pulmonary oedema

Pulmonary oedema is a condition in which fluid accumulates within the normally air-filled alveolar space resulting in impaired pulmonary gas exchange. This usually results from increased hydrostatic pressure in the pulmonary venous circuit.

The most common cause associated with pulmonary oedema is left ventricular failure (LVF). In LVF, there is reduced ejection fraction with increased end-diastolic volume and cardiac pre-load. The pooling of blood and increased pre-load causes an increase in left atrial pressure and pulmonary venous pressure, and consequently increased pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure. The increase hydrostatic pressure causes increased nett filtration of water out of the capillaries into the pulmonary alveolar space.

Common causes of LVF include myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathies and myocarditis.

In addition, cardiac arrythmias such as atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachyarrhythmias and heart blocks may cause reduced ejection fraction and pulmonary oedema.

Dysfunctional mitral and aortic valves may also contribute to pulmonary oedema. The obstruction of blood from the left atrium in mitral stenosis or the left ventricle in aortic stenosis can lead to back-pressure to the pulmonary vein, with increased pulmonary venous and capillary hydrostatic pressure causing pulmonary oedema.

In non-cardiogenic oedema, there is damage to the lung parenchyma that causes increased capillary permeability and escape of not only water but also plasma proteins and inflammatory cells into the alveolar spaces, or an exudate.

Non-cardiogenic exudative pulmonary oedema is seen in conditions such as acute lung injury and associated acute respiratory distress syndrome

Occasionally pulmonary oedema, which is transudative, may occur not primary due to cardiac decompensation due to intravascular volume expansion as may occur in chronic and kidney injury, transfusion associated circulatory overload and in severe hypoproteinaemia.

Congestion

Hyperaemia and congestion are two terms you would often hear when talking about blood flow and circulatory changes. Both are associated with collection of blood in the capillaries, but they refer to different phenomena.

In hyperemia, arterioles actively vasodilate to increase capillary inflow in response to a stimulus such as exercise, inflammation, allergies or heat exposure. Its’ usually a physiological response, and the vasodilatation serves to increase blood flow to meet the metabolic demands of the tissue. The inflow of blood into the capillaries should equal the outflow and there is no blood stasis although the vessels appear engorged. The affected area usually appears flushed and warm due to the increased blood flow.

Congestion however is a passive process and is usually pathological. In congestion there is an accumulation of blood in the tissue or organ, consequent upon impaired outflow from the area. The outflow may be obstructed due to local causes such as venous thrombosis or systemic cause such as congestive cardiac failure.

The obstruction causes trapping or stagnated blood in the capillaries with disruption of tissue oxygen delivery, leading to tissue hypoxia and sometimes cyanosis. Blood vessels are distended and engorged with oedema tending to occur together because of increased venous hydrostatic pressure from the blood flow obstruction.

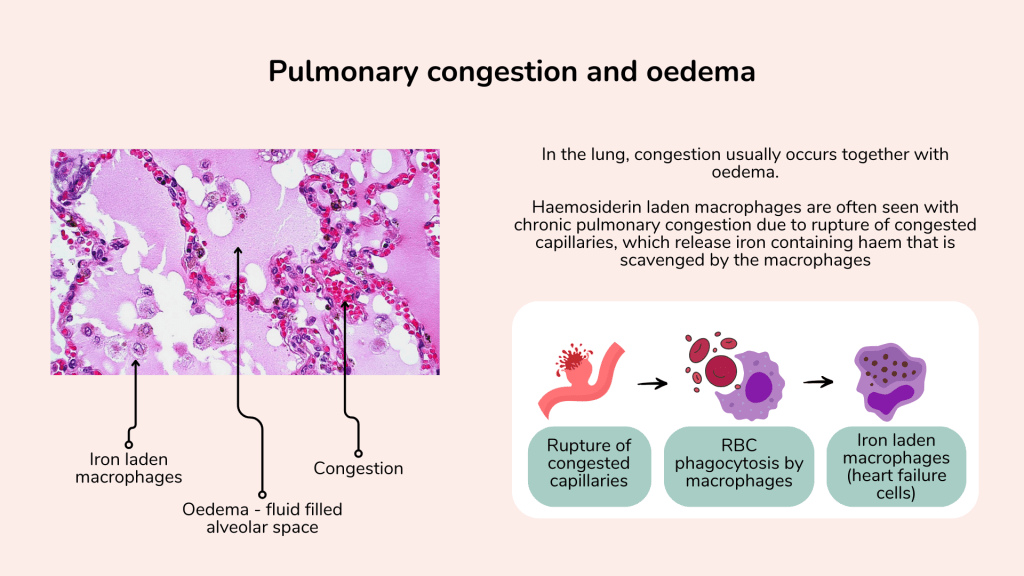

Pulmonary congestion

Congestion in the lungs is a feature often seen in association with pulmonary oedema. This is because pulmonary oedema most commonly results from left ventricular failure or left valvular disease that obstructs the outflow of blood from the lungs through the pulmonary vein and the left cardiac chambers

In addition to the engorged dilated pulmonary blood vessels due to congestion, and fluid filled alveolar spaces associated with pulmonary oedema one may also appreciate the presence of haemosiderin laden macrophages in chronic pulmonary congestion.

This occurs due to rupture of the congested capillary, which release the red cells into the interstitial and alveolar spaces. The red cells are phagocytosed by tissue macrophages, releasing the iron which remains in the macrophage, giving rise to the iron laden macrophages, sometimes referred to as heart failure cells.

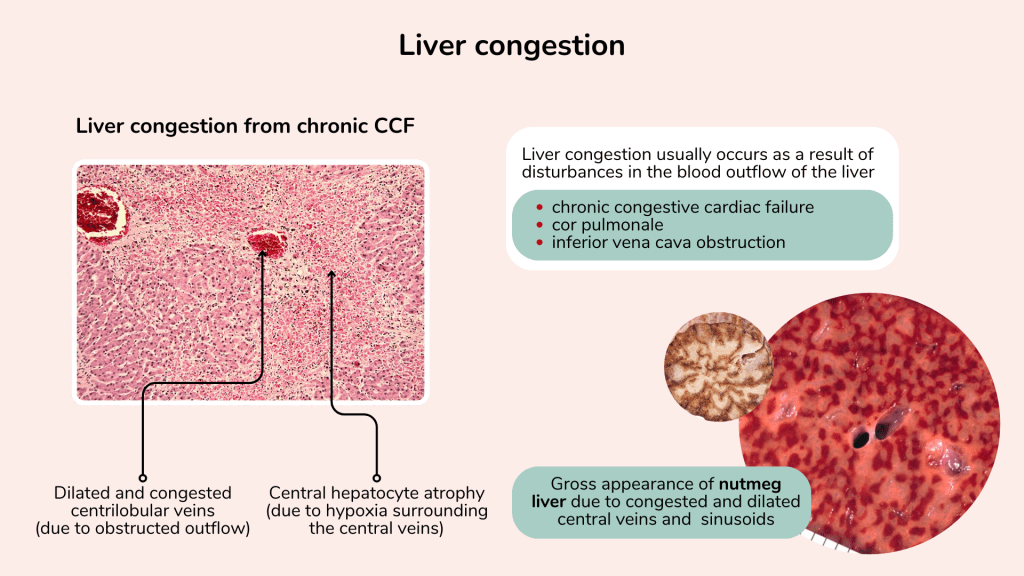

Liver congestion

Liver congestion usually occurs due to disturbances to its blood outflow. Common causes include congestive cardiac failure, cor pulmonale and inferior vena cava obstruction.

Chronic congestion in the liver is observed as dilated engorged centrilobular veins due to the obstructed outflow.

In long standing liver congestion, central hepatocyte atrophy is seen because the cells surrounding the central veins experience chronic hypoxia. Grossly, cross section of the liver may show a nutmeg appearance due to the congested and dilated central veins and sinusoids, which resembles the appearance of a sliced nutmeg seed.