- Learning outcomes

- What is thrombosis?

- Factors that prevent clotting in blood vessels

- Virchow’s triad

- Arterial vs. venous thrombosis

- Complications

- What can happen to a thrombus?

In the ancient Chinese medical text, ‘Huangdi Neijing (黄帝内经)’, written over 2000 years ago, the fundamental concepts of circulation is stated – ‘All the blood is under control of the heart. The blood current flows continuously in a circle and never stops.’

Blood must be in constant flow. It needs to flow continuously so that it can deliver oxygen and perform its myriad function throughout the body. In order to flow, it must remain in a liquid state while it travels through the blood vessels. However, blood vessels can get cut, injured or rupture. When that happens, blood needs to clot at the damaged area so that the the injured area is sealed and blood does not escape from the blood vessel.

Various components of blood (coagulation factors, anticoagulants, platelets) and the blood vessel lining (endothelium) interact to ensure that blood remains liquid while in-flow but can clot to plug holes in the vessel wall when required. This exquisite balance can however be disrupted by various conditions, leading to the abnormal solidification of blood in intact blood vessels, a process called thrombosis.

In this blog, we will learn about how thrombosis occurs and its consequences.

Learning outcomes

- Explain the term thrombosis.

- Illustrate how various factors can contribute to thrombus formation, using the concepts described by Virchow also known as the Virchow’s triad

- Differentiate the risk factors, appearance and consequences of thrombosis occurring in the arterial (left-sided) and venous (right-sided) circulation

- Describe the potential fates of a thrombus

What is thrombosis?

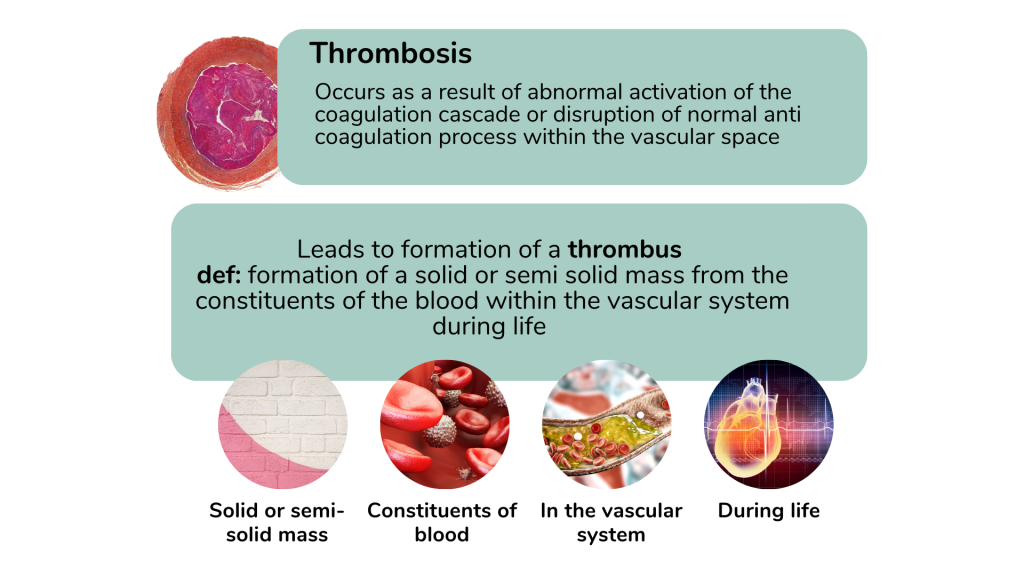

Thrombosis (v.) is the formation of a solid or semi solid mass from the constituents of the blood within the vascular system during life. By definition, a thrombus (n.) must be within the intact vessel and the process should occur while alive. This is a pathological condition as under normal physiology, clot propagation should not occur within the blood vessels.

Blood that solidifies outside the blood vessel such as following a bleeding cut or when blood is placed in a sample tube, is termed as coagulation or clotting and cannot be called thrombosis.

The formation of a solid mass will result in obstruction or impediment to blood flow, leading to serious clinical consequences such as myocardial infarction, stroke, gangrene and sudden death.

Factors that prevent clotting in blood vessels

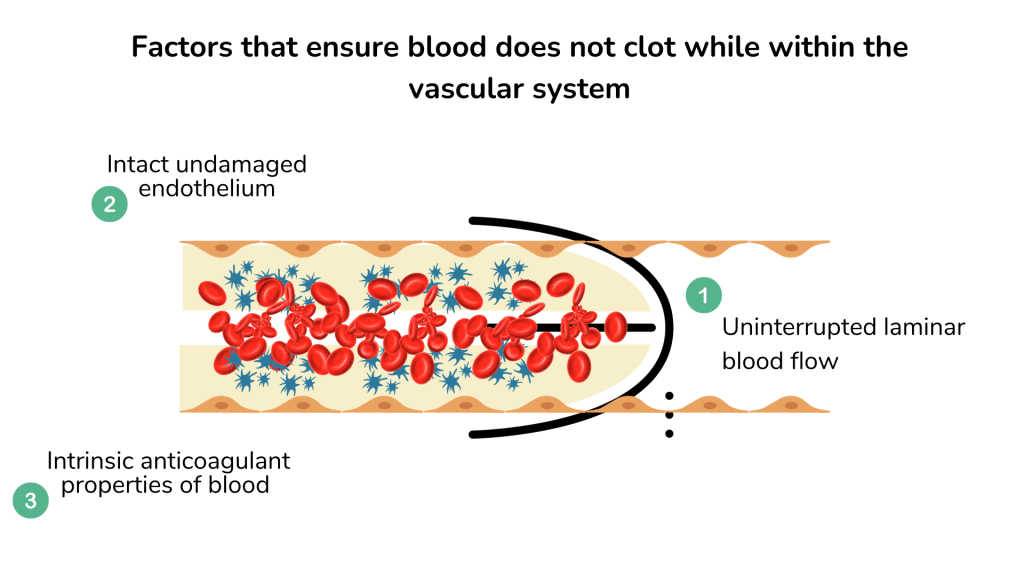

1. Laminar blood flow

In fluid mechanics, laminar flow refers to the smooth passage of liquid in layers, with each layer passing smoothly over the adjacent layer with little or no mixing. The velocity of blood flow is highest in the central layers and slowest adjacent to the vessel wall, giving rise to a parabolic flow profile.

The laminar flow partitions the different components of blood within the flowing bloodstream. Adjacent to the endothelium lining of the blood vessels is the plasma layer that separates the platelets from directly interacting with the endothelial surface.

Platelet activation and adhesion to endothelial cells is an important initiation step in the formation of a thrombus. Red cells meanwhile flow within the central axial core.

When there is narrowing of the blood vessel or irregularities on the surface, such as from a venous valve or an arteriosclerotic plaque, the laminar flow is disturbed, leading to a turbulent flow and presence of eddy currents. This brings the platelets closer to the endothelial surface and activation of the platelets, leading to thrombus formation.

2. Anticoagulant properties of endothelium

The endothelium lining of the blood vessel acts as a natural barrier to prevent the blood from clotting in the blood vessel. Endothelial cells express prostaglandins, thrombomodulin and heparin-like substances that prevent activation of platelets of the coagulation cascade. They also express tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) that promotes the breakdown of clots that may form.

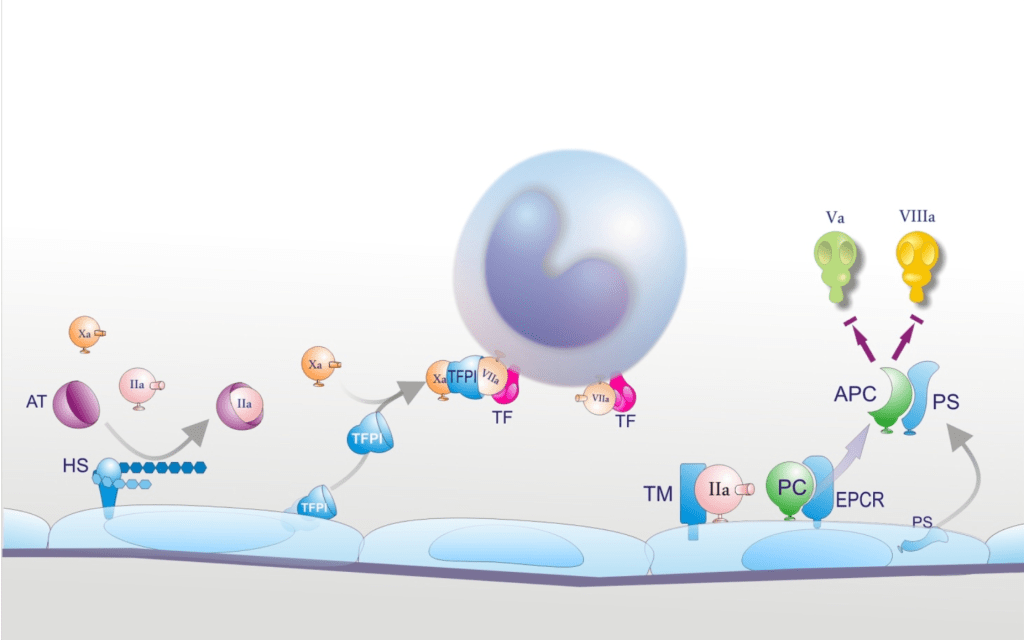

Anticoagulant properties of endothelial cells. Heparan-sulphate (HS) is expressed on the endothelial surface and accelerates the interaction between antithrombin (AT) and its target enzymes, among which factor Xa and thrombin (IIa). Thrombomodulin (TM) and endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) are also membrane proteins and are involved in protein C (PC) activation. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and protein S (PS) are released into blood. TFPI, after combining with factor Xa, binds to and neutralizes the TF/VIIa complex on cell surfaces. Protein S is the cofactor of activated protein C (APC) which degrades factors Va and VIIIa. (Semeraro, N., Ammollo, C. T., Semeraro, F. and Colucci, M. (2010) “SEPSIS-ASSOCIATED DISSEMINATED INTRAVASCULAR COAGULATION AND THROMBOEMBOLIC DISEASE”, Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases, 2(3), )

Damage to the endothelium exposes the flowing blood to sub endothelial structures such as collagen that can initiate thrombus formation. In addition, the damaged endothelial cells also release substances such as tissue factor (TF) that activate the coagulation cascade and platelet to form a thrombus.

3. Soluble anticoagulants in plasma

Plasma contains various coagulation factors that initiates and propagates coagulation. However, uncontrolled coagulation is dangerous. In the normal physiological state, once the vessel damage is sealed by a clot, such as following a cut, the coagulation process needs to be terminated and the clot gradually removed as the wound heals. The control and termination of coagulation is facilitated by natural anticoagulants such as tissue-factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), antithrombin (AT), protein C (PC) and protein S (PS). Plasminogen meanwhile is converted to plasmin to dissolve the blood clot (thrombolysis).

Deficiencies of any of these natural anticoagulants can predispose an individual to form thrombi.

Virchow’s triad

Disturbances to the physiological control of haemostasis, as outlined earlier can result in a predisposition to thrombosis. The factors that predispose to thrombosis in conveniently classified by the Virchow’s triad that was first proposed by Rudolf Virchow in the nineteenth century.

The triad basically refers to disturbances in the three elements that we had described earlier.

- Stasis

- Endothelial or intravascular vessel wall damage

- Hypercoagulability due to functional or quantitative abnormalities of soluble plasma factors

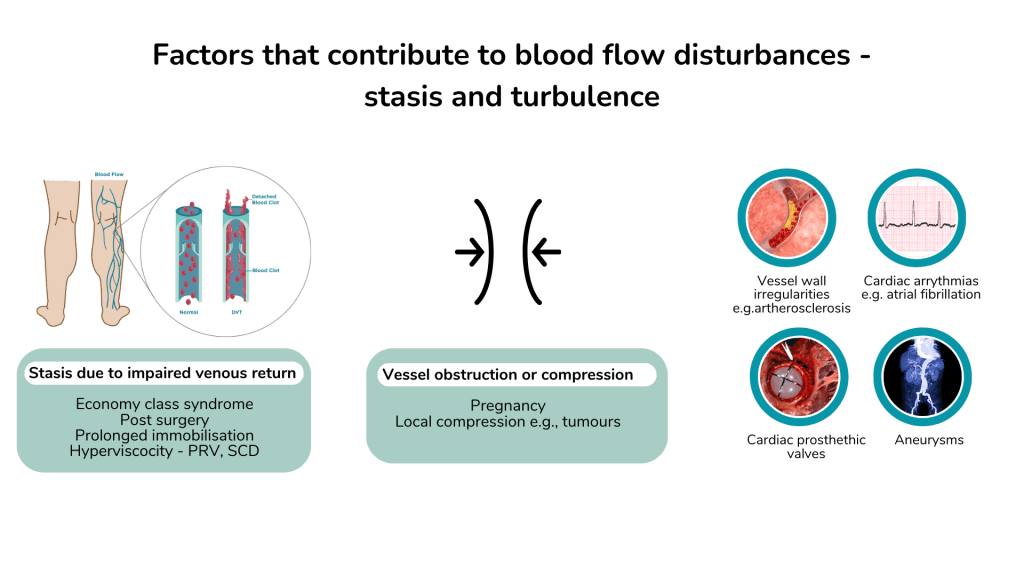

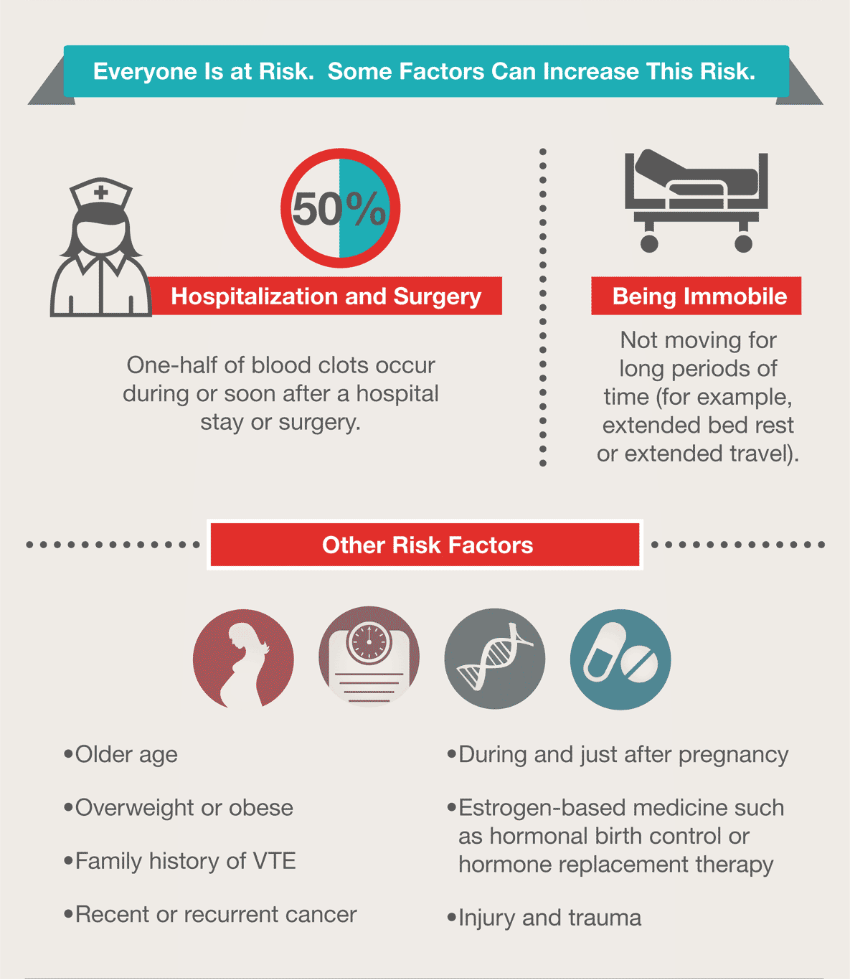

1. Stasis and alterations to blood flow

Blood that is not flowing in the blood vessel has a propensity for clotting., as coagulation and platelets are activated and the anticoagulant properties of the vessel wall diminishes with prolonged contact. Factors that cause stasis include;

- Prolonged immobilisation e.g. bed-ridden patients, post-surgery and delayed mobilisation, long-haul travel (economy class syndrome) , trauma

- Atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, myocardial dyskinesia or aneurysms leading to pooling of blood in cardiac chambers or aneurysm sac

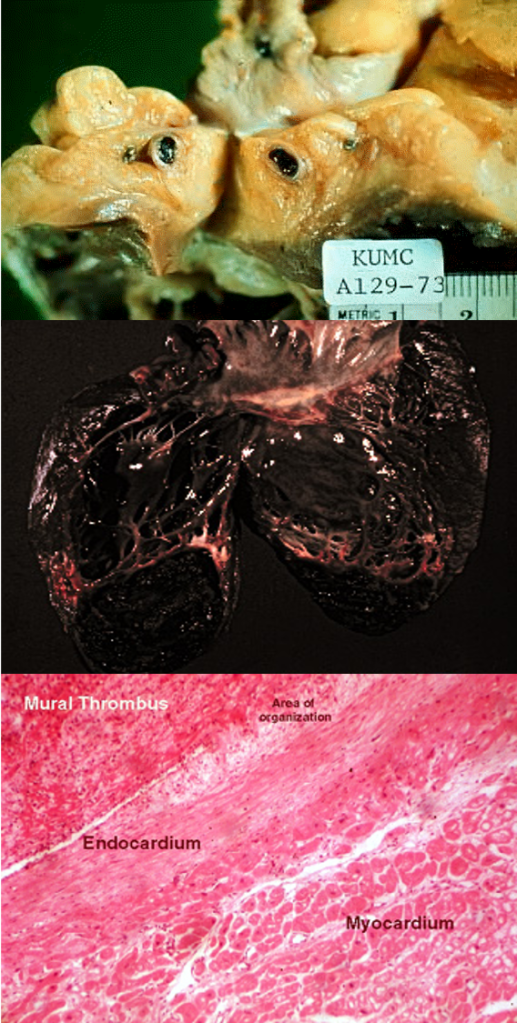

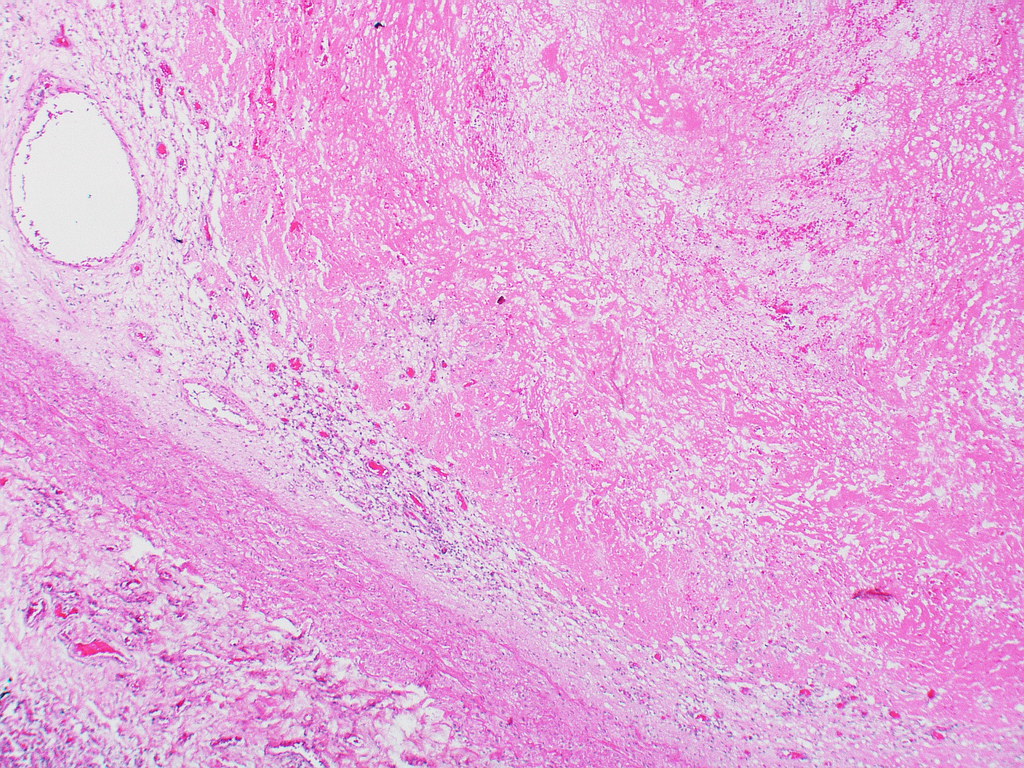

Thrombosis that occurs with stasis secondary to prolonged immobilisation is often seen in the large blood vessels such as the deep veins of the leg. Stasis occurring in the cardiac chambers due to muscle dyskinesia or in an aortic aneurysm usually appears as a mural thrombus, where the thrombus is attached to the wall of the blood vessel or cardiac chamber.

- CT axial image of an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm with intraluminal thrombus.

- Corresponding, massive, intraluminal thrombus removed during open surgical repair. (Piechota-Polanczyk A, Jozkowicz A, Nowak W, et al. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2015;2:19)

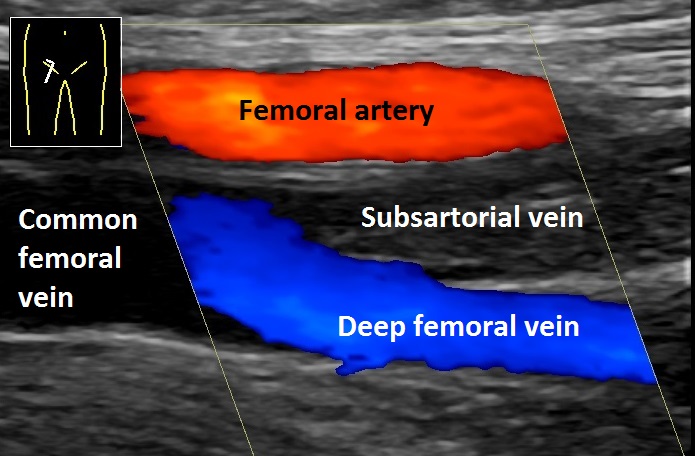

- Doppler ultrasonography of the right leg of a 65 year old man with a swollen right leg. It shows deep vein thrombosis in the subsartorial vein. There is absence of blood flow as well as hyperechogenicity in the thrombosed vessel, as compared to the deep femoral vein and the femoral artery. (Mikael Häggström, M.D. – Author info – Reusing imagesMikael HäggströmConsent note: Written informed consent was obtained from the individual, including online publication., CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

2. Endothelial or intravascular vessel wall injury

Damage to the vessel wall causes alteration to the blood flow. The surface may be irregular and this would create a turbulent flow resulting in increased risk for thrombus formation. Atherosclerosis is the principal risk factor for arterial thrombosis. Damage to the endothelial may also be secondary to smoking, surgery, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for acute coronary thrombosis leading to myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. Smoking is associated with endothelial activation causing an imbalance in its antithrombotic properties with increased procoagulant effect.

Various systemic inflammatory diseases associated with vasculitis e.g. Behcet’s disease, giant cell arteritis, are associated with an increased risk of both venous and arterial thrombosis. In these conditions, the endothelium show increased expression of procoagulants and tissue-factor which may provoke thrombosis.

Thrombosis associated with endothelial injury is more commonly seen in the arteries as compared to the veins. Atherosclerosis associated thrombosis is only observed in arteries.

3. Hypercoagulability

Physiological haemostasis is dependant on proper functioning and balance of platelets, coagulation factors and anticoagulants. Thrombosis may occur in the following circumstances;

- Platelets are increased in numbers (thrombocytosis) e.g. myeloproliferative neoplasms

- Platelets are hyper-functioning e.g. heparin-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (HITT), vaccine-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenia

- There is an increase in procoagulants and reduced anticoagulants e.g. pregnancy, oral contraceptives, drugs, malignancies, lupus anticoagulants

- Inherited deficiencies of anticoagulants e.g. antithrombin, protein C, protein S deficiency

Thrombosis associated with hypercoagulable states can occur in both arteries and veins, although venous thrombosis tends to be more commonly associated with these conditions.

Arterial vs. venous thrombosis

Thrombosis may occur in arteries or veins. However, as arteries and veins have different functions and properties, the type of thrombi that occurs in them also have different pathology and consequences.

Arterial thrombosis

The arterial system of the circulation is high pressure and fast flowing. The arteries are also prone to atheromatous changes.

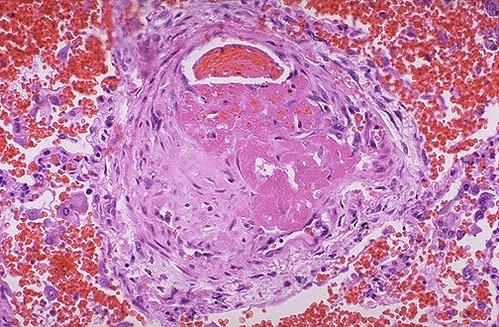

Thrombi in the arteries are usually pale in appearance as they consist mainly of platelets and fibrin that adhere to the arterial wall. Red cells are not trapped in the thrombi as they are swept away by the fast moving flow of blood.

In a large thrombus, alternating layers of platelets and red cells may be seen, which is termed as lines of Zahn.

Arterial thrombi tend to be occlusive and obstruct the flow of oxygenated blood into the region supplied. This can cause ischaemia or infarction of the organ. The thrombus may also detach and embolise to a distant organ. These concepts of ischaemia, infarction and embolism will be covered in a future blog.

Common sites of arterial thrombosis and their consequences include;

- Coronary artery – angina pectoris, myocardial infarction

- Cerebral artery – transient ischaemic attacks, stroke

- Peripheral arteries – peripheral vascular disease, limb gangrene

- Carotid artery – cerebral thromboembolism, stroke

Common causes of arterial thrombus include atherosclerosis, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, and hypercoagulable states.

Venous thrombosis

In contrast to the arteries, venous blood flow is slow and is of low pressure. Blood in the extremities needs to flow against gravity. Blood flow in the veins especially from the lower extremities towards the inferior vena cava, is facilitated by the pumping action of the calf muscles and venous valves that prevent back flow of blood.

Stasis of blood due to immobilisation, prolonged venous compression and hyper coagulable states are major causes of venous thrombosis.

Venous thrombi are usually friable and appear red in colour due to the numerous red cells that get trapped in the forming thrombi.

The most common site of venous thrombosis is in the deep veins of the legs, which include the popliteal, femoral and iliac veins. Thrombosis in these areas are referred to as deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

The major complication of DVT is venous thromboembolism (VTE) and pulmonary embolism (PE). These aspects will be covered in a future blog.

Complications

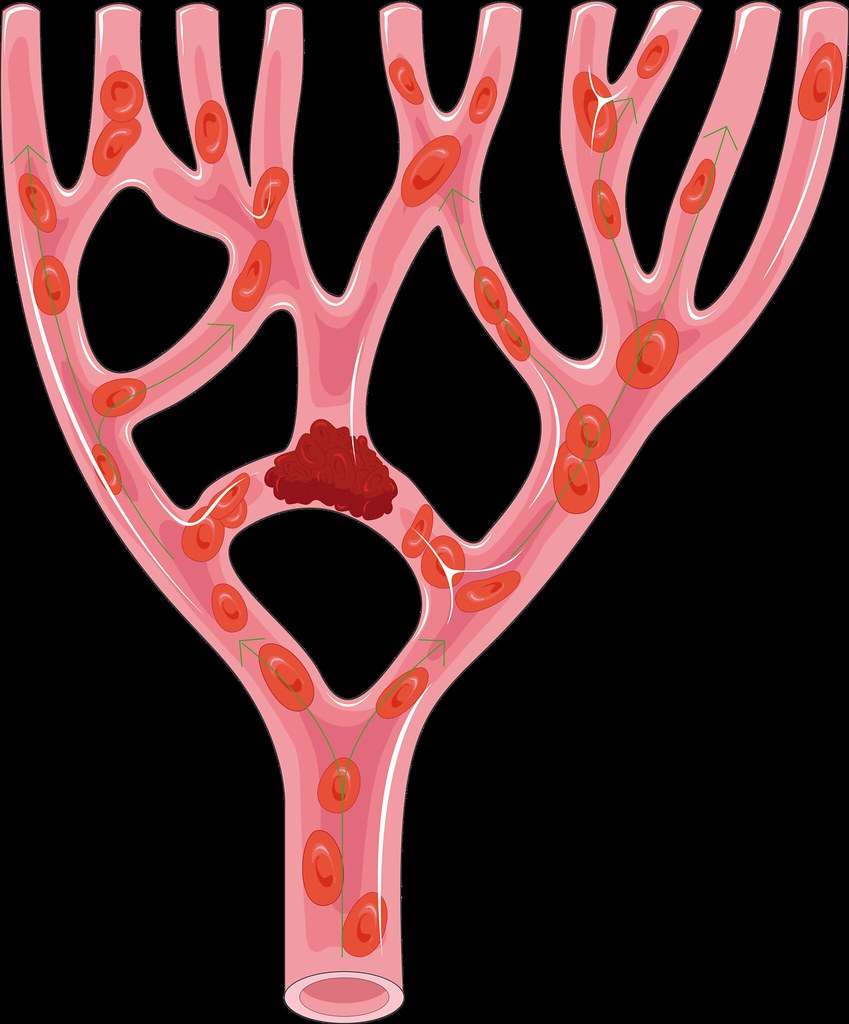

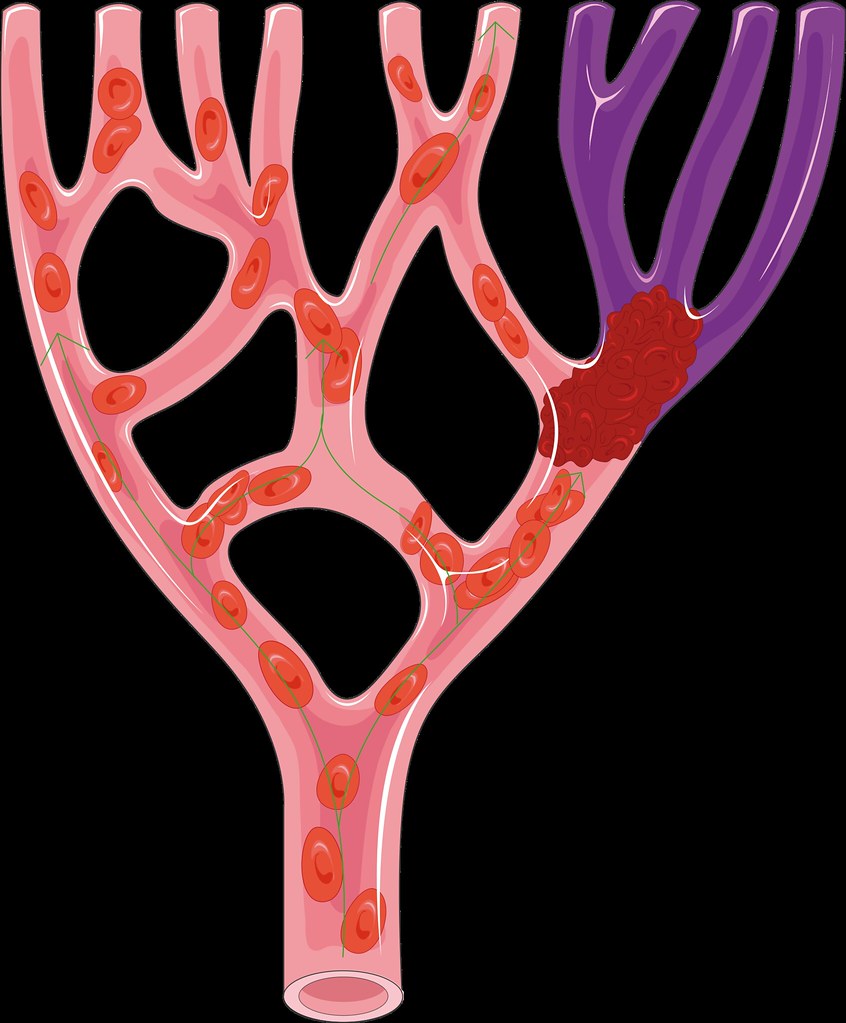

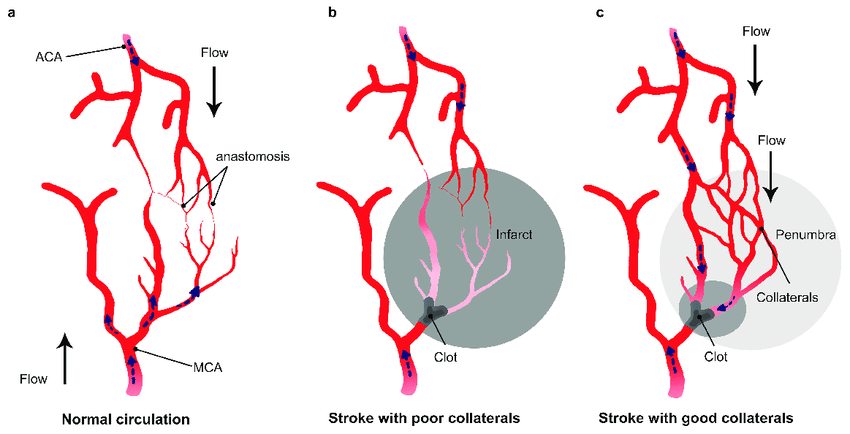

A thrombus may persist, causing occlusion of the blood vessel. In the case of an arterial thrombus, this occlusion would cause a lack of blood flow to the supplied organ. If this is an end-artery, such as in the spleen or kidney, infarction may ensue, leading to necrosis of that part of the organ. However, if collateral circulation (e.g. coronary circulation), or a dual blood supply (e.g. portal vein and hepatic artery in liver) is present, ischaemia is likely if the thrombus is slow-forming.

In an acute thrombotic event such as coronary thrombosis following plaque rupture, leading to myocardial infarction, there may be insufficient time for collaterals to form and compensate for the reduced circulation.

- Thrombus occluding a crossing branch of an artery causing minimal disturbances to blood supply as blood continues to be supplied by the adjacent branches. 2. Occlusion of a terminal branch causing disruption of blood flow and infarction. 3. Re-establishment of blood flow following a thrombotic event by growth of collaterals into the area disrupted by blood flow (Amki, Mohamad & Wegener, Susanne. (2017). Improving Cerebral Blood Flow after Arterial Recanalization: A Novel Therapeutic Strategy in Stroke. International journal of molecular sciences. 18. 10.3390/ijms18122669. – available via license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International)

A thrombus can also detach, either in part or as a whole and be transported to a distal part of the circulation. This is termed thromboembolism and the phenomenon will be discussed further in a subsequent blog.

What can happen to a thrombus?

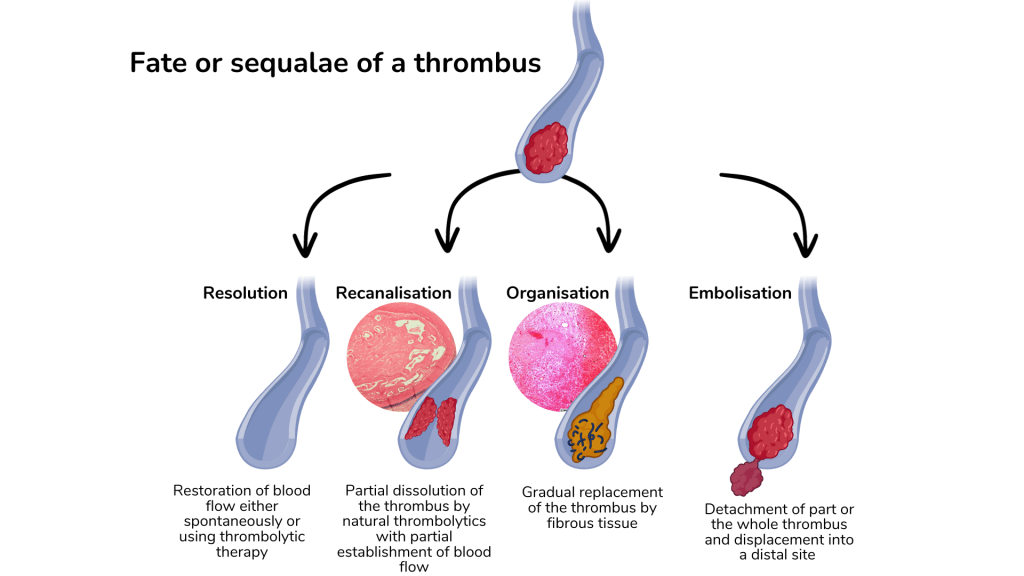

The thrombus may progress or regress depending on local and general factors. Briefly they may have five different outcomes.

- Progression – the thrombus continues to grow in size as more platelets, red cells and fibrin are added. This is particularly common with deep venous thrombosis

- Recanalisation – inherent fibrinolytic activity may dissolve parts of the thrombosis to allow partial reestablishment of blood flow through the created fenestrations

- Resolution – small thrombi may be dissolved either through in-vivo fibrinolytic activity or by therapeutic interventions e.g. thrombolytic therapy, angioplasty

- Organisation – long standing thrombi may gradually undergo a process of healing and repair and be eventually replaced with fibrosis

- Embolism – the thrombus may detach and be transported distally in the circulation

Dr. Veera! Hello! I know it’s a good day and I think I found a typo. Atheroscelorosis… atherosclerosis…

LikeLiked by 1 person